Introduction

Having worked in the social care sector for many years, predominantly in residential care with looked after children, I began a Master’s Degree in Educational Improvement, Development and Change (Residential Care of Children and the Skills of the Social Pedagogue).

In 2010 I began working as a Home School Support Worker (HSSW) and was invited to develop the role in a primary school located in a deprived area in a coastal town in Yorkshire. This paper explains how I tackled this, and discusses the emerging results.

Any names used in this paper have been changed to protect the individual’s identity.

Demographics

Within the locality of the school there are numerous single-parent families, a high rate of unemployment and many young people not in employment, education or training (NEET). The postal code for the area has approximately 1500 residents.

In August 2011, 913 crimes were committed in this area, consisting of more than 500 anti-social behaviour offences and approximately 300 drug-related crimes. This demonstrates a crime rate above the national average. At the time of this study, there was a police presence at the school gates at the beginning and end of each school day.

School Population

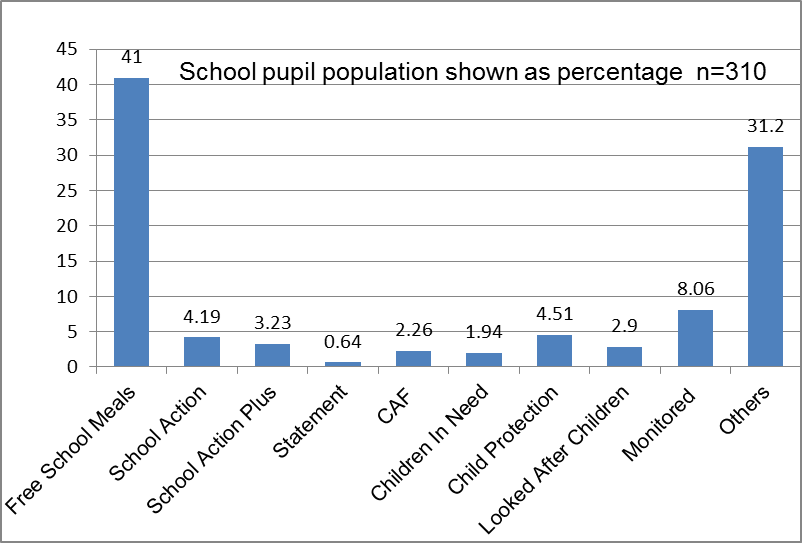

At the time of the study there were 310 pupils on roll. The whole school attendance was at 89% with 50 pupils in the persistent absence category.

CAF: Common Assessment Framework

As you can see from the above chart there is a high percentage of children having free school meals and a significant number of children identified as having emotional and behavioural needs.

Deprivation is a key aspect of life in this school. We have a breakfast club which is free for children to attend, as a consequence of so many children coming to school without eating. Forty per cent of the school attends each day on average.

In addition, as a school, we often have to purchase items of clothing for children who are dressed inappropriately according to the weather. Last winter, one child attended school in flip flops in the snow.

Communication

Initial observations within the school suggested to me that, there was a distinct lack of methodical and constructive communication. Reporting of school absence was inconsistent and often not followed up. Although policies and procedures were in place they were not often adhered to.

Thinking outside the box

Inspiration can come in many forms; this quote struck me as simple yet a meaningful metaphor.

A compost heap is a particularly complex organic structure where constituent parts interact with one another to produce compost. When this interaction goes well the result is a medium for growth; when something within the biochemical process goes wrong it can let off a stench.

It does not take too much imagination to extend this metaphor to residential childcare; as a form of intervention with children, it can be a powerful medium for growth or at worst, it can become decidedly rotten. Within an ecological model, interventions in one area may well produce unintended consequences elsewhere in the system. (Smith, 2009:87)

It does not take too much imagination to apply this metaphor to the workplace. Social pedagogy as a form of intervention with children can be a powerful medium for growth.

Resource development

We can only begin to address a problem once we understand its cause. To enable me to understand the cause I developed a simple yet effective attendance matrix. This method of analysis soon highlighted groups of children whose attendance was a concern.

When compared with the school population as a whole, I identified that children who received additional support in school and those whom the school were monitoring but were unknown to services also had attendance issues. This simple yet effective method of data analysis has enabled me to streamline abundant data into focussed target groups.

This method is utilised by the school as a method of precision monitoring. It defines the whole school attendance percentage, accounts for how many children are PA and easily shows what actions are being taken to address a specific problem.

Simple but effective.

|

Date/ Term |

Attend-ance % |

PA |

Circum-stances |

Action |

Impact |

PA: Persistent Absentee

Moving forward

· Methodical Approaches

Having identified these issues I decided that, in order to address them I needed to group individuals’ needs into categories, and from there devise ways of approaching their problems.

The categories are Individual Child, Small Group and Whole School.

· Improving communication

The need to improve communication was imperative. As we all know, constructive communication is key to the success of any working environment. Discussions between school staff and myself needed to be structured and more frequent.

Initially there seemed to be a lack of understanding about my role as their Home School Support Worker. I also put in place a reporting procedure to ensure I was informed of individual children’s absences daily.

· Identifying Vulnerability

The process of identifying vulnerable children was streamlined; this was achieved by analysing patterns of attendance and behaviour concerns with school. This flagged up a list of children who required some kind of intervention.

These interventions were also categorised as Individual Child, Small Group and Whole School.

Therapeutic Approaches

· Individual Child

This consisted of working 1:1 with each child and working through a life journal together. This enabled us (the child and me) to explore their lives as they saw it and work through possible difficulties together. At the beginning of each session we would revisit the record of our feelings. This provided the child with actual evidence of progression of feelings. Life journal work proved invaluable and was deemed a positive influence by the children and their families.

I would meet with children in school, and also with the children and their families in their own homes, sharing their life-space to discuss positive management of behaviour and emotions. The outcomes were generally positive, and mostly, parents were receptive.

In most circumstances, the child’s behaviour appeared to be a consequence of either poor parenting and or family lifestyle choices. However, working with the family unit has improved communication between parent and child and parent and school. This has improved attendance and behaviour. Some of these children who I felt might need additional support were selected for the small nurture work programme.

· Small nurture groups

During analysis of the school population, I identified groups of children with similar needs and/or concerns. These children were placed into small groups and allocated one hour per week of non-curriculum time with myself.

This project was run over one term per group and the aim of the group was to create their own ‘worry buddy’.

Most people would want to know ‘what is the significance of a worry buddy’. First, the initial aim was to create a buddy or little friend that the children could use as a comforter, or even confidante. But, once we break down this activity into stages we realise that there is so much more to it. The groups had a maximum of six children whose behaviours were considered to be an issue within the school.

The first session consisted of an introduction to my worry buddy Brian, what I talk to him about, and why he is my buddy. I then introduced a wide variety of materials and we discussed what materials we like and what we would like to use.

The first session is probably the most difficult as the children don’t know what to expect. The majority of these children can appear distressed when they need to make a choice or decision. Choices do not play a significant part in their lives at home.

Being presented with a large tray of buttons to choose from can silence the group, their excitement tangible. They can pick what they want, it’s a small action, but it’s very empowering. Sitting together, supporting the group to communicate with one another positively is fascinating, watching group dynamics unfurl, the introvert becoming more confident, the extrovert calming and engaging in the activity and talking to their peers.

There have been many positive outcomes from this group exercise.

Children, who once feared older children in the playground, feel confident in talking to an older child as they may have been in a group together. They appear to feel more socially acceptable amongst their peers.

Although there are far too many wonderful moments to list, there are two significant instances which have stayed with me which I would like to share with you.

Jake is six; I had an established relationship with Jake, as his attendance had been a problem.

After carrying out a home visit in an attempt to locate him, I found him at home with his brother, their mother intoxicated and unconscious on the sofa. I waited with the children while the police arrived and the children were removed under a Police Protection Order . Jake and his brother were placed in foster care. Jake and I shared that experience, and it created a bond.

Jake found his transition into care hard and he became withdrawn.

After a few sessions within the nurture group, another child told the group he was excited; he had ‘contact’ with his mum that evening. Jake asked the boy what he meant by ‘contact’ with his mum. The boy replied, “Oh, I’m in foster care”.

Jake began to cry. I was concerned and I comforted Jake and asked him what was wrong. His answer, “I thought there was only me in this foster care thing”. He was crying with relief.

Henry is eight. His family have been known to Police and Social Services since his birth and his home life is very chaotic. Consequently, Henry is a very chaotic child with significant challenging behaviour.

Initially he was reluctant to engage in the group activity, and it became apparent that Henry seemed afraid to pick a sock and buttons in case they “weren’t the right ones”. He presented as very insecure and lacked self-confidence. After some cajoling and encouragement Henry engaged well, and was actually very good at sewing.

We eventually came to a crucial point in our worry buddy-making process. Henry, who was difficult to engage with, was known as being difficult, challenging and unwilling to contribute, but he was the first to name his buddy. He called him Fred, “because he was made out of thread”. It was lovely to see the pride on Henry’s face.

After feeding back this progress and input to curriculum leaders, Henry’s Individual Education Plan was altered to accommodate his previously misunderstood low self-esteem.

· Whole School

Whilst working with individuals and small groups, I began to fully absorb the large number of children affected by dysfunctional and chaotic lives.

Negativity is like an infectious germ. There was an overall sense of acceptance amongst the children: this is my life; that’s the way it is.

I really wanted to try and inject some enthusiasm and ambition into the school population, hoping to improve self-belief in individuals and consequently improving attainment.

I needed a message that good attendance at school would help them achieve their ambitions. It was at this point, in my search for resources, that I stumbled upon something I thought was perfect: a song.

The song was used in each class, every week to accompany their respective ‘wake and shake’ times. At the end of term I held a whole school assembly and played the song with its video on a large screen.

The reaction to the song was brilliant. None of the children had seen the video, but they knew the words, and everyone joined in and sang along. When it finished it prompted a question and answer session with the children.

Albeit a brief intervention, it captured the imaginations of the children and it is still used as a tool of encouragement. It’s funny how the children will still refer to it as Mrs Proudman’s song.

Vulnerable Children

• Skills Transfer

Having worked with vulnerable children and their families for many years, first as a detached Youth Worker and then as a Residential Child Care Officer, I became accustomed to reading familiar behaviours presented by children and young people. My ability to read a situation, pre-empt a reaction and understand the inner workings and complexities of individuals is fine-tuned.

It is without doubt that my experience gained while working in residential care has equipped me with a variety of skills and knowledge, which I have been able to transfer to my current post as an HSSW. Although the school staff has a duty to report matters of concern to the relevant services, they didn’t always see things that I did. It seemed that I was identifying potential concerns for children whom school staff had not considered to be vulnerable.

My ability to communicate effectively and network whilst reading a child’s behaviour and presentation has proven invaluable on many different occasions. I have chosen just two case studies as examples of the value of skills transfer within the post of the HSSW.

• Toby

Toby was five, a very likeable child, and quite clingy with adults. He had an older brother in school who had behavioural problems, and an older sister whose attendance was very poor with sporadic unexplained unauthorised absences.

I had spoken to the children’s mother on many occasions and didn’t seem to be getting any results with her daughter’s attendance. Around the same time, Toby started soiling himself.

When their mother was approached about the soiling incidents, she stated that Toby did this on purpose because he was a naughty boy and such a horrid child.

All three children presented as dishevelled and unclean and were beginning to get teased by other pupils because of their smell. Toby continued to have accidents, and became distressed. On one occasion he begged support staff not to tell his mum what had happened. Again, Toby soiled himself, and this time refused to be changed. School contacted mum to collect him. He returned to school the following day in the same pants with faeces stuck to his skin. This was reported to the Designated Senior Professional for Child Protection (DSP).

I contacted mum again; I advised her that I had concerns for her and her children. Her daughter’s attendance was not improving and Toby’s incontinence was getting worse. I offered her support, suggested a referral be made to the School Nurse, and asked whether she would consider a meeting to discuss a positive action plan of support to try and help her turn things around. The children’s mother refused all of the offered support, and the following day, all three children were absent from school. I decided to do a home visit.

I knocked on the door, and saw one of the children through an upstairs window, but nobody answered the door. I continued to knock, and eventually the door was answered.

I was greeted with a hideous wall of smell which made me take a step back. The children’s mother was angry that I had visited her at home and went to close the door. I advised her that I needed a visual of the children before I left, so she shouted the boys. Both boys were filthy, and in dirty clothes, they said they were okay and didn’t know why they weren’t at school. I then asked to see their sister.

The mother sent the boys upstairs telling them to go and get their sister. She then walked away from the front door and into a back room leaving me standing on the doorstep. After a short while the boys came running downstairs saying they couldn’t find her. The daughter then appeared from the back room with her mother close by. I found this quite odd: why did she send the boys upstairs when she knew where her daughter was? I asked the girl how she was feeling, and why she wasn’t at school.

Her mother answered every one of the questions.

I smiled at the family and thanked them for their time; I advised that I looked forward to seeing them all in school tomorrow. I got back to my car and tried to piece together this jigsaw of information and what it was telling me. Something wasn’t quite right.

When I returned to school I relayed this information to the DSP. I felt concerned for the children’s welfare and something just was not right. Was I making assumptions or was I utilising my inner skills base, or was it both? Concerns were passed on to Children’s Social Care; the information was logged.

Then there was a breakthrough, a disclosure of historical and on-going sexual abuse by a family member towards all three children. The children were removed and it was reported by the team involved that the adults would defecate on the floor, hence the smell that greeted me on the day of my visit. The father of the children has since been jailed for twelve years.

• Bella

Bella was nine. She did miss a day of school in two years. Bella tried hard with her school work, was eager to please and in general was a lovely child. Sometimes Bella presented as slightly subdued, but overall she seemingly enjoyed school.

Bella’s Mother was known to come into school on occasion, and ask to talk to the Head about Bella’s behaviour problems. She painted a picture of an incredibly difficult child who fought with her younger sister, was disrespectful and mum claimed she could not cope with Bella.

At the request of the school, I contacted Bella’s mum, and asked her if she would like to meet up and discuss her problems. I explained to Bella’s mother that school had no concerns regarding Bella’s behaviour or academic progress. However, her younger sister aged five was getting into trouble for pushing, fighting and refusing to listen at story time.

This triggered an unexpected response.

Bella’s mum was angry; she told me that it was the other way around. When she talked about her youngest child there was a look on her face of love, adoration and pride – a loving parent. But, when she talked about Bella, she changed. She looked disapproving, she said Bella was an “evil child” and asked me, “What was she to do?”

I was very honest with Bella’s mum, and told her what I’d observed when she talked about her children and the differences she had expressed. Tearfully, Bella’s mum acknowledged what I said and stated, “I just don’t like her. It makes me feel guilty”.

Armed with this information, I was able to offer Bella’s mum and the children a package of support. This involved a referral to use the Common Assessment Framework to explore family therapy opportunities, and I also began a programme of therapeutic life journal work with both children individually. I engaged with their mother in 1:1 discussion as a means of discovering the root cause of her problem with a view to improving the family unit.

Although poor school attendance can be a key indicator of potential problems, it’s not a blanket rule. If we listen carefully, and observe what is around us, we as practitioners can unravel complexities that, without which we would undoubtedly miss.

On Reflection

When I first took this post as a Home School Support Worker there was no clear job description. It was very much a case of ‘See what presents itself in school and take it from there’.

From the initial problem of dealing with attendance issues developed a complex and varied set of circumstances that required continuous support and attention. The pedagogic approach enabled me as a HSSW to expand the role into more than merely an attendance monitor. It provided positive social opportunities far too numerous to mention in this brief paper.

When I consider my caseload I know that I am working in an edge of care environment. To be able to help resolve a situation and keep a family unit together at these early stages must be a positive move forward.

When you consider that approximately 6,000 children per year are taken into care, any approach that works toward reducing this number must be a worth-while venture.

There is overwhelming evidence within my primary school to support the need for a Home School Support Worker with experience of working within the social care sector; this I see clearly as a Social Pedagogue.

Jade Proudman is a Master of Arts in Educational Improvement, Development and Change, having also studied at post-graduate level in the Skills of the Social Pedagogue and Holistic Approaches to Education and Wellbeing in Residential Environments. She has been a Home School Support Worker, a Residential Centre Worker in a children’s home with looked after children, a Detached Youth Worker in rural communities and a Trainee Youth Worker, working with vulnerable children locally and in Romania.