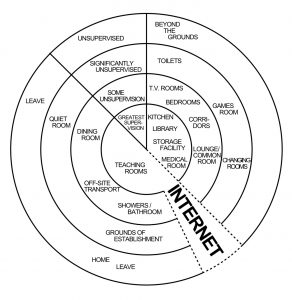

In the first paper of this series ‘Residential Care and Education for Children and Young People under the age of 18’ all sectors of such care were identified and illustrated in a model. The model indicates the significant diversity of provision for those being educated away from their home. For those readers who may not have previously seen the model it is included once again here.

Model 1.

It is difficult to accurately provide data indicating the numbers of individuals within each sector. Even if that data was forthcoming it would soon be out of date. For example there are fewer young people detained within custodial settings than previously (see Youth Custody data available on-line from His Majesty’s Prison and Probation service. Youth Justice Statistics 2019-2020 states ‘The number of first time entrants has fallen by 84% since the year ending December 2009, with a 12% fall since the year ending December 2018.’). Likewise, the number of young people residing in Young Person’s Hostels may be more difficult to measure and may have increased in number (given the daily influx of refugees, some of whom will be of schools age, entering the country each week).

Context for this paper.

Some 25 years ago The York Group gave a series of lectures to practitioners in residential schools – from boarding schools through to residential children’s provision with education. At that time a significant topic to bring to the attention of all staff was around staff on pupil abuse in a residential setting. From rather limited knowledge it appeared that abuse could happen in some environments and the need to challenge, document, report and deal with it was immensely important. The response to the presentations was mixed. Delivering the talk from the front indicated facial expressions and nods (of understanding) as well as the occasional shaking of heads, suggesting from the audience ‘I think I know what you are alluding to’ right through to ‘that would not happen in my school’. [The latter caused greatest concern, where there was denial this could lead to harbouring, excusing and even ignoring that abuse was taking place].

Sadly our concerns were wrong. The sheer scale of the abuse that has occurred over time – and continues to – has been way beyond that anticipated. Of great regret is in not shouting much louder all those years ago and not preventing the ongoing abuse which continues to be reported, (including those enquiries in Northern Ireland and currently in England and Wales).

No one can be in any doubt about the scale of Child Abuse which has occurred in residential educational establishments over a significant period of time. The purpose of this paper is not to further highlight this aspect (staff on pupils). This has been documented elsewhere with best practice, documentation, involvement of outside bodies [LADO]. A key lesson is in not being complacent; and constantly reviewing current best practice and incorporating that best practice at a local level. The whole ambiance around child abuse has changed – massively for the better – but complacency will undermine and destroy the progress made.

Staff on pupil abuse is therefore being targeted. Looking back now we can see where mistakes were made, how the language of abuse then (as in the past) was either negligent or nonexistent. There was no excuse then, there certainly is no excuse now for any establishment to not know their legal and moral responsibilities.

What has happened in the past cannot be undone. It is unforgiveable that it happened. Only best practice will prevent it from occurring in the future.

The purpose of this paper is to explore child on child abuse. Rather like staff on child abuse, there are comparisons:-

- It is likely that it has been under reported

- It has been ‘dealt with’ sometimes inappropriately or not at all

What is needed is to explore the different settings within residential establishments of such abuse and generate discussion around lessons learned from the past and how to enable the prevention of such abuse going forward. This is a difficult area to document and talk about but just as with staff on pupil abuse of the past unless there is openness and honesty in discussions we can’t make the necessary progress.

The Independent Inquiry Child Sexual Abuse published their investigation report titled “The residential schools investigation” in March 2022. The focus on this report was:-

Phase 1: Music schools and residential special schools,

Phase 2: Safeguarding: day and boarding schools.

The executive summary states “The instances of the sexual abuse of children presented in this report will shock and horrify.”

On boarding schools, the section on ‘Additional risks at boarding schools (C:2 p59)’ states:

“Pupils at boarding schools are also at heightened risk of harmful sexual behaviour between children at school because of the increased opportunities for such abuse to take place.”

On Residential Special Schools, (Part D:4 p74) ‘Harmful sexual behaviour’, states ‘Harmful sexual behaviour between pupils occurs in all types of school but can be a particular issue in residential special schools where pupils who are living together may have difficulties understanding social cues or appropriate interactions.’

Later in the report the section ‘Responding to allegations and concerns in England’, E.2: Background; paragraph 6 refers to DfE document ‘Keeping children safe in education 2021’ (statutory guidance for schools and colleges) this was further updated in September 2022. Part five: ‘Child on child sexual violence and sexual harassment’ states that ‘sexual violence and sexual harassment can occur between two children of any age and sex…..(paragraph 447) and all staff working with children are advised to maintain an attitude of ‘it could happen here’’ paragraph 446.

A further document published by the DfE “Sexual violence and sexual harassment between children in schools and colleges. Advice for governing bodies, proprietors, headteachers, principals, senior leadership teams and designated safeguarding leads” September 2021 identifies in Part three: “A whole school or college approach to preventing child on child sexual violence and sexual harassment.”

It is not the purpose of this paper to collate recommendations from these and many other recent reports. The concern of this paper is how to better prevent any child on child abuse in a residential education setting. The aim is separate from documenting best practice or justifying a case – these have been addressed in the above reports and the documents they refer to and quote from. It is high time to accept that there is a problem and begin to unpick how this may be addressed and prevented.

Two models are proposed to help indicate where the problem may occur and also how the physical structure of buildings (and more) may contribute to the problem.

Plan of residence.

Model: EWA Model

This diagram is an attempt to cover the range of spaces which might be found in residential settings. Depending upon the purpose, the plan for a boarding school would differ from that of a children’s home, a hospital school or a young offender institution. Freedom of access to the different spaces would also vary and this will dictate the level of supervision deemed necessary.

It is reasonable to suggest that children resident in educational establishments would have the most freedom (of access to spaces) and those in custodial settings the least. Contingent upon the reason for residence, children in social or medical care, access may be anywhere between the two extremes.

In all types of residence, the kitchen and the medical room will be supervised and the teaching rooms, library, dining room and any storage rooms are likely to be locked in the absence of supervision. In the shared recreation areas, the common room and the quiet, TV, games, changing and drying rooms, staff presence may vary but the need for supervision to guard against unacceptable behaviour is generally acknowledged. However, it in the sleeping areas the showers and baths, the lavatories and the grounds that staffing presents obvious problems and abusive and harmful behaviour can most easily occur.

Vulnerability of different areas of residence.

Model: Vulnerability of different areas of residence, NMC Model

This model attempts to identify those areas within an establishment that offer greater and lesser degrees of safety as a consequence of their location or input.

Five distinct areas are outlined.

Greatest Supervision.

Even within the most stringently supervised environment, abuse can take place. (The recent conviction of a retired head teacher found guilty of sexual abuse of boys at the front of the class, fifty years ago, when made to stand by his desk, confirms this). Even under the tightest scrutiny the potential for abuse remains. This should never be forgotten or overlooked. As the model indicates there should be less likelihood of such abuse in these areas by virtue of adult supervision throughout time. A child/children should surely never be left unsupervised in any of the locations identified. It is imperative that all these rooms are secured when not in use.

Some Supervision.

Using the mindset of ‘it could happen here’ must be applied throughout all areas identified in the model. This becomes a greater possibility as we move from the centre of the model.

Each establishment will need to risk assess all areas in terms of numbers of pupils and supervision by staff. This has always been the case. Great care needs to be used in making sure who is responsible for the learner’s at different times of the day. Is the teacher solely responsible during teaching hours? What about lunch times and break times – are other staff, house parents, nurses, teaching assistants responsible at these times? Who supervises the lounge/common room, corridors and so on? To what extent is cctv used – or not, walkie talkie radios? How are lines of sight ensured at all times? Are there any areas/corridors/rooms which can be unseen/hidden/abused?

The above also applies to offsite transport. Is the education provider (school) solely responsible or do house parents, nurses, other adults with such responsibility take over, and if so how and when. (Is there a ‘gap’ between supervision, there shouldn’t be).

Showers and bathrooms should have their own risk assessment, fully understood by everyone within the establishment. Assuming they are single sexed facilities there remains scope for misdemeanour and worse. Which staff can enter such rooms? Who also needs to be present? Why? Should this be documented? If not, why not? Each establishment needs to have their own risk assessment and policies here. These in turn must be a priority (along with many other risk assessments and policies) for new members of staff – and children, going through an induction programme to the institution. Staff and children need to understand why these are in place.

Television Rooms may require less supervision – dependent upon the layout of the establishment. Most (not all) establishments may identify a lesser supervision here – as in a reduced number of staff, or ‘passing attention’.

Significantly Unsupervised.

These areas offer much greater potential for misdemeanours to take place. There will also be different concerns dependent on the establishment. Young Offender’s Institutions are likely (and should) have far greater supervision to unstructured areas than some education facilities. If we consider once again ‘it could happen here’ – how could it happen here? If coercion of an individual has been used, if they ask to go to the toilet/games room/grounds – is there the potential for a perpetrator to also be present? Toilets should require less supervision but are things in place to make sure they are safe areas?

Unsupervised.

This is that difficult area – beyond the boundary of the school/education building, both nearby and further afield. Who has the responsibility on say the top deck of a bus, on home leave, for those who might be entitled to, trips unsupervised beyond the grounds of the establishment? How in turn might this be found out about as well as impact upon the establishment on return?

Internet.

This broad heading encompasses all aspects of the internet which allow communication – email, social media and web sites and so on. An immensely useful tool when put to proper use, greatest supervision of the internet is likely to take place towards those areas at the centre of the diagram, for here are likely to be fire walls and more to prevent inappropriate access to material. Most education provision has strict rules as to what internet access is deemed appropriate within that establishment along with how it may be blocked as well as recording any inappropriately accessed material and the means of access (which computer, or equivalent and the time/location etc).

As we move further away from greatest supervision so the boundaries as to what might be accessed can become blurred. Inappropriate material can be accessed (on mobile phones and tablets) scurrilous and anonymous accusations may be made about an individual; scenes set, scenarios and locations hijacked. This in turn may impact anywhere within the model, especially any area perceived by a perpetrator as a safe (momentarily or otherwise) place to cause abuse.

The Internet is not some sort of requirement for abuse to take place but it would appear that an easy means to enable it and should not be underestimated in its potential.

This is terrifying. There is no escape from ‘it could happen here’.

Obviously there is a need for whole staff training. By that we mean not just the teachers, technicians, classroom assistants and more, but all staff in the establishment: business secretaries, playground supervisors, caretakers, chefs, medical staff, everyone. Unlike some forms of staff training which may be annually delivered by online access (child protection is frequently delivered this way) child on child abuse requires a whole establishment approach – including governors or their equivalent. Such training should also be integral to initial induction training. All staff have the responsibility of being whistle blowers. There can be no complacency. If any member of staff feels they have any concerns in this area they must be made aware of the establishment’s protocol in dealing with it.

This is an extraordinary difficult subject and area to address. We have barely touched the topic here. Our concerns around delivering the required training and altering any whole establishment mindset (‘it couldn’t happen here’) are significant. As indicated at the start of this paper there are many reports and recommendations coming through as this awful area is finally getting long overdue attention. Teachers do not have ever more time to take another massive area of concern on board. They do need accurate and succinct guidance, training and opportunity to discuss their own working environments and beyond.

To that end we recommend as follows.

REPORTS.

The continuing current ‘Independent Inquiry Child Sexual Abuse’ has generated many reports and findings, frequently around abusive behaviour in schools and focussing on staff misbehaviour; and also misconduct by children and young people in day school. There are major concerns raised that apply to young people in residential settings. There is clearly the need for a detailed review of abusive behaviour by children on children in residential education and care.

The York Group research concluded that, within the residential and care system, there are

19 distinct settings (Model 1, above) – a figure subsequently recognised by the Residential Forum. Each has unique features but to provide a report for each setting would be expensive and would involve extreme repetition. If all 19 were in one volume, the report would unwieldy and many parts would be unused by most readers. It is therefore suggested that similar settings should be grouped together producing four reports: educational, custodial, health and social.