This article originally appeared in the journal ‘Educational Therapy & Therapeutic Teaching’ the journal of the Caspari Foundation.

There is currently a great deal of concern about children who are failing to thrive in our schools through difficulties around both learning and behaviour. One could say that these children lack self-awareness, self control and a sense of agency. Sometimes, changing the environment in schools or at home can make a difference – as described elsewhere in this journal. For some children, however, particularly those who may have had poor early attachments and traumatic experiences of abuse, loss or neglect, problems have become internalised and direct therapeutic work is indicated.

In this article I give an overview of educational psychotherapy, a method of assessing and treating children and young people. This intervention, which bridges the gap between education and therapy, grew out of the work of Irene Caspari, a psychologist at the Tavistock

Clinic in the 1960s (Caspari, 1980). Importantly, the concepts informing this approach can be translated into the classroom where they are very helpful to teachers (Salmon and Dover, 2007).

Twelve year old Claire was referred to a Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) because she was disruptive in school and failing to learn to read. Psychometric tests confirmed that there were no specific deficits to account for her educational difficulties. There had, however, been a great deal of loss and trauma in Claire’s family. Her father had died slowly of cancer and her mother, a depressed and fragile woman, struggled to care for Claire and Claire’s severely disabled older brother.

Claire was offered an educational psychotherapy assessment. In her stories, drawings and approach to tasks, she showed that she felt responsible for people close to her – as if her own angry feelings might have damaged or destroyed them. She drew a picture of her family with the use of a ruler in an attempt at rigid control – as if free expression might be disastrous. She worried about breaking her pencil and messing up her exercise book. When attempting to read, she watched her therapist’s face closely to monitor her reaction to mistakes.

As is the case with many insecure children, some of the processes and content of the curriculum had become imbued with special meaning for Claire. It was clear that literacy aroused anxiety in her and that manipulating symbols such as letters or words felt risky. She appeared to confuse destructive fantasies with the healthy aggression needed to learn – to ‘tackle’ a word or ‘break it down’ into its component parts. In addition, she believed that the adult teaching her would not be robust enough to manage her mess, muddle and mistakes. It was likely that Claire had lacked an experience in infancy of containment and reciprocity and that she struggled with hostile feelings towards a mother to whom she was insecurely attached. Since there was clearly an emotional component to Claire’s failure to learn, the chosen treatment was educational psychotherapy.

How are children who may benefit from educational psychotherapy identified?

As we saw with the example of Claire, the therapy targets children with chronic difficulties around learning that persist despite the special needs help offered in school. In order to learn, children need to feel safe enough to accept the powerlessness of not knowing and to trust the adult teaching them. For those whose internal or external worlds are dangerous, this may feel too risky. Teachers are aware of ‘something underneath’ that needs to be addressed before the children can benefit from what is on offer in the classroom.

Commonly, the impact of the children’s problems on their education is that the child may

present in school as any of the following:

■ Depressed and withdrawn

■ Restless and unable to concentrate

■ Unable to verbalise thoughts and feelings

■ Expressing emotion through violent and disruptive behaviour

■ Struggling with aspects of the curriculum or basic skills

■ Academically underachieving

■ Unable to relate to peers or teachers

■ Refusing to attend school or at risk of exclusion.

Who are the therapists?

Educational psychotherapists are experienced educators with an additional clinical training (UKCP registered). As a framework for their work, therapists are profoundly influenced by psychoanalytic concepts. Winnicott’s (1965) and Bion’s (1962) ideas about early learning and maternal ‘containment’ and ‘reciprocity’ – and Melanie Klein’s (1957) thoughts on infantile aggression, are of particular interest. In addition, therapists increasingly draw on research from attachment theory and neuroscience.

What are the basic beliefs underpinning the work?

The work is based on the premise that emotional factors and learning are closely connected and need to be addressed together – and that bringing the unconscious impact of learning into a child’s conscious awareness, frees a child to develop and learn. Early experiences of learning and relating in infancy continue to affect taking in information and relating to a teacher. We now know that the very structure of the brain depends on early experience with a carer (Moore, 2007). Getting alongside a child, in the context of an important relationship, to unravel the meaning of his difficulties, promotes increased self awareness, learning and self-control.

Where and how does the work take place?

Children are seen individually or in a group for this intervention. The work can take place in a clinical setting such as a CAMHS – but because of its educational focus and structured nature, it is also highly congruent with an educational setting. As already mentioned, the concepts and some techniques informing the work are also very useful to a teacher in the classroom.

What is unique about the work?

The use of structured imaginative activities and the learning task are features that distinguish educational psychotherapy from child psychotherapy. Education and the meaning of difficulties in the educational arena remain the focus of the work. The therapy benefits children who are unable to tolerate and use an unstructured therapeutic contact. Avoidant children in particular, respond well to a therapy that includes a task which acts as a buffer enabling the child to regulate proximity to the therapist. The therapist works through the

maternal transference while the task provides a limit setting paternal function (Beaumont, 2000). A fundamental feature of the work is an emphasis on using the metaphor or ‘working at one remove’ rather than always making direct interpretations. An example of this might be

discussing the feelings of a character in a child’s story. This suits very fragile children and those harbouring family secrets.

What happens in an educational psychotherapy session?

■ Secure base and space for reflection

Regular sessions take place in a quiet, confidential setting. The therapist offers a reliable and consistent presence, preparing the child for breaks, providing a ‘facilitating’ environment’ (Winnicott, 1965) and fostering a sense of safety.

■ The transference/attachment

The therapist notices how the child relates to her and the feelings he elicits. Using her observations and her knowledge of early attachment, she resists being drawn into modes of relating which might recreate the child’s early experience. She aims to provide a different experience with a significant adult. Importantly, she accepts both the positive, loving and the hostile, negative feelings brought by the child – so that he feels his ‘true self’ is acceptable. Claire’s case demonstrates how angry feelings, perceived as unbearable, often get in the way of learning. She benefited from sessions with an adult who could withstand and survive her hostility. The fact that these feelings could be communicated to

the same person who was teaching her, helped Claire to feel sufficiently safe to learn.

■ Direct teaching and Adapting the Task

As said earlier, the structure imposed on the session by direct teaching is an important part of the work. Observing a child’s responses to formal learning enables a therapist to identify defences affecting learning. Claire, as we saw, avoided making demands on a teacher or risking mistakes. By ‘tuning in’ sensitively to what the child can tolerate and where he is in his emotional development, the therapist provides a safe setting in which the child can try out new skills. Only gradually does she introduces educational challenges, ensuring that the frustration

which accompanies learning is never overwhelming. Tasks are tailor-made to ensure some success, giving the child the self-validating experience of correct anticipation and potency, often for the first time. The therapist uses her observations and understanding of the child

to adapt teaching strategies to his needs. For example, she may use competitive games when teaching a child whose hostility or envy towards her, get in the way of learning.

■ Expression work

‘Expression work’ is fundamental to the sessions. Through curriculum subjects as well as stories, games, play and drawings, the child is encouraged to express his deepest feelings and thoughts. Everything he does and says is accepted as a communication of his concerns or preoccupations. These are explored through the metaphor, so that they can be clarified and worked through. Children are adept at communicating in this way. One child, for instance, revealed his illicit knowledge of a family secret through a drawing. He depicted a terminally ill brother with Angel’s wings. This child had resisted reading because, for him, it represented independent access to knowledge. Another child created an imaginary ‘twin’ who was to carry all the abused aspects of herself. This defence, which relied on keeping good and bad things separate, affected her capacity to integrate information.

■ Building a narrative

The therapist’s responses to the child’s communications echo the containment and reciprocity of mother/infant interaction and can be through words but also through choice of activity. She seeks to get alongside the child in a non-intrusive way and collaboratively build a coherent narrative about the child’s life. Ultimately, a child becomes more self- reflective. As Jeremy Holmes (2001) says, therapy is about both making stories and breaking stories.

What training do educational psychotherapists offer other professionals?

An important role of an educational psychotherapist is to increase awareness of emotional factors affecting children’s learning and behaviour through providing training to professionals such as teachers, learning mentors and educational psychologists. Training is delivered through long or short term courses delivered at Caspari – the Professional Organisation – or externally.

What are the clinical outcomes for children receiving educational psychotherapy?

Educational psychotherapy is an effective intervention for troubled children struggling with learning.

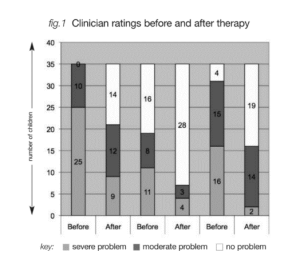

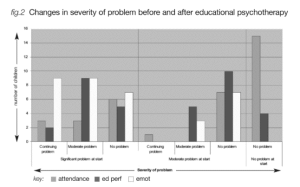

There follows an excerpt from a small-scale audit of work by three educational psycho-therapists working a total of 12 sessions (6 days) a week in a CAMHS, over a two year period. During this period the therapists saw 106 children comprising 37 for longer-term therapy, 10 for educational psychotherapy assessments only – and 59 for multidisciplinary interventions. The following graphs are based on the 37 longer term cases.

Educational psychotherapy looks for three overarching primary outcomes:

■ Improved attendance/inclusion in school

■ Improved educational performance

■ Psychological and social wellbeing.

These outcomes are summarised in the following charts (overleaf). The first chart shows clinician rated outcomes on these domains before and after therapy. Clinician ratings are based on feedback from the child’s school, parental reports on the child’s behaviour and learning and observations of the child in therapy. This indicates that, at the completion of therapy, the number of children rated as having a severe problem was significantly reduced compared with the start of therapy and that these reductions occurred in all three domains of functioning.

The second chart shows the same data organized according to the severity of the problem at the start of therapy. For example, this shows that of the children rated to have a severe problem with respect to emotional well-being (n=23), approximately a third remained unchanged at the end of therapy on this domain (n=9), a third showed some improvement (n=9) and a third showed substantial benefit (n=7). 16 children were rated as having severe problems with respect to capacity to learn. At completion of therapy, 2 children continued to be rated as unchanged, 9 had improved and 5 were functioning at an age appropriate level. The point of this method of describing outcome is that it separates those children who, at the beginning of therapy, were not rated as having a problem in a particular domain and therefore gives a more balanced assessment of overall improvement.

fig.1 Clinician ratings before and after therapy

fig.2 Changes in severity of problem before and after educational psychotherapy

A more detailed description of educational psychotherapy can be found in Reaching and Teaching through Educational Psychotherapy: A Case Study Approach. Salmon, G. and Dover, .J. (2007) Wiley.

Further information about clinical services and training in educational psychotherapy can be found through the website www.caspari.org.uk or through contacting the administrator at Caspari on 020 7704 1977.

References:

Beaumont, M. (2000) Attention Deficit Disorder: Making Good the Deficit. Educational Therapy and Therapeutic Teaching. Issue 10. London. Caspari

Bion, W. (1962) Learning from Experience. London. Heinemann

Caspari, I. (1980) Learning and Teaching. The Collected Papers of Irene Caspari. London. Caspari

Holmes, J. (2001) The Search for the Secure Base. Brunner-Routledge. Hove and New York

Klein, M. (1957) Envy and Gratitude. London. Tavistock Publications

Moore, M.S. (2007) Building the Brain with Procedural Knowledge. Educational Therapy and Therapeutic Teaching. Sept 2007, Issue 15. Caspari Foundation

Salmon, G. and Dover, J. (2007) Reaching and Teaching through Educational Psychotherapy: A Case Study Approach. Wiley.

Winnicott, W. (1965) The Maturational Process and the Facilitating Environment. London. Tavistock