The theme of my action research is the teaching and learning during a National Lockdown when schools were responsible for organising and delivering a minimum of 3 hours a day of remote learning to children in KS1 and 4 hours in KS2 (Department of Education, 2022). UNESCO (2021) reported that more than 1.37 billion children from 190 countries were forced to transition to remote learning instead of in-person education during the outbreak of COVID 19. This was a stressful time for teachers, pupils and parents who had very little time to prepare (Khlaif et. al. ,2021).

I started at the Mulberry Bush, a therapeutic community, school and residential care home for children aged 6-13 who have experienced early childhood trauma 2 months before the first national lockdown. Being relatively new to the organisation, I was expected to transition to remote learning and then deliver one-to-one lessons with children who had previously thrown pencils at me when I had asked them to sit down. Although the guidance is clear that educators at SEND schools are best placed to know about what is best to meet the children’s needs, it still implies that children in these settings should receive remote education (Department of Education, 2022). Becker et al., (2020) recognises that engagement in remote learning varied but children with mental health and/or learning difficulties found it particularly challenging. Class adults and children at the Mulberry Bush School found remote learning challenging: adults had less ability to scaffold the learning experience for the children (Juuti, 2021) and children had to be resilient to the changes in a task that they already found difficult. However, I’m not sure I agree with Chzhen et al., (2022) who describes how remote learning has damaged many children’s engagement with school. This was not my initial experience.

I chose to investigate this area of my practice because I noticed an improvement in engagement by a child I met twice a day for 2 months during the first lockdown, Kelly. Kelly sparked my curiosity. In Kelly’s final placement report at the school before she left the school in June 2020, it mentioned her engagement in the remote learning and how over this period, she had begun to read out-loud when she had previously never done this. Before the remote learning period, Kelly was the child throwing pencils at me. Over the remote learning period in March 2020, Kelly went from having 3 x remote learning sessions a week to having 2 x a day. Unfortunately, as this child has left the school, there is no longer enough reliable data to include her in this research.

I chose to look at engagement and remote learning for several reasons. First, working with these children, I am particularly interested in what engages them. Engagement has been linked to positive outcomes and high educational performance (Veiga et al., 2016) and is a predictor of children’s success at school (Lee, 2012). For me, engagement can be active or passive. A child’s passive involvement in their learning could be more of a compliance to complete the task – there is less actual engagement and the child’s behaviour indicates a lack of interest and a lack of involvement in the task. Whereas active involvement in their learning requires them to comply with school and class rules, persist in concentrating, and exhibit self-directive behaviour (Cadima et al., 2015). The children at the Mulberry Bush find this all very, very difficult. Perry and Szalavitz (2006) discuss how children who have experienced trauma, have a sensitized stress-response system which causes them to respond to normal situations as if it is threatening. Essentially, as they enter a classroom, Mulberry Bush School children’s Frontal Cortex and Limbic systems responsible for abstract and emotional thought are switched off and the Brainstem, a reflexive part of the brain, is activated which pumps stress hormones around the body; heart rate speeds up in order to direct oxygen to the muscles in preparation for fight, flight or freeze (Perry and Szalavitz, 2006). Typically, children at the Mulberry Bush School struggle to learn in a classroom. Many of the children referred to the school have been excluded from mainstream schools on multiple occasions because their behaviour was too challenging to manage. Classrooms are scary, loud places and learning requires a submission and a tolerance of uncertainty (Bion, 1969). Learning requires a dependency (Bion, 1969) and for the children at the Mulberry Bush School, uncertainty in the past has hurt them and healthy dependency doesn’t exist because it hasn’t been modelled and then internalised by having a consistent, good enough caregiver (McLeod, 2017).

The period of remote learning provides me with an entirely different context to analyse engagement with these children: in-person in the classroom and remotely online, in a home environment. I say home environment instead of at home because some of the children in this research were accessing their remote learning in the 52 week provision at The Mulberry Bush for children who don’t have foster, adoptive or biological parental figures. These two entirely different contexts provides an opportunity to compare the engagement in the learning in two different contexts. Through this, I may be able to unpick factors that affect engagement for children who have experienced early childhood trauma.

My precise questions is:

How did remote learning affect the engagement in Curriculum subjects of 7 children at the Mulberry Bush School?

I chose to research engagement because it is a process that creates a direct path to learning (Cadima et al., 2015). For me, engagement can also be apparent in a person’s behaviour so it can be observable (Juuti, 2016). We can see this in the way that a child may ask questions and be curious, contribute to the lesson and comply (Veiga et al., 2016).

For this study, I have chosen to focus on 7 children who were all in the same class during the January/February 2021 school lockdown. For the most part, the children were taught by the same teacher before and during the remote learning periods. Therefore, it is less likely that other variables (like change of teaching styles) affected the children’s engagement before and during the remote leaning period. However, it is important to note that a few of the children (3 out of the 7) moved class after the remote learning periods. This will be discussed later in the Evaluation section.

I have not chosen to study the first period of remote learning (March 2020 – June 2020) because the children are no longer at the school and there is less access to data required for this research. I have also chosen not to look at the most recent period of remote learning (March 2022) because it was only 3 days long and there is not much documented about the remote learning sessions. The January/February (2021) period of remote learning is the most consistent period of remote learning with the least amount of variables affecting the data.

This enquiry question is relevant and significant for my professional development. I will reiterate how important engagement is for children in order to maximise their learning opportunities, especially online (Tualaulelei et al., 2021). Naturally, as a teacher working with children who have difficulty engaging in their learning, it is part of my responsibility to understand what factors impact engagement for these children. Researching the impact of remote learning on engagement could inform practice and attempt to find a creative, innovative way to engage these children. Are there aspects of the remote learning period that we can adopt in our day-to-day teaching of these children, in-person and remotely?

This enquiry question is also relevant for my school and organisation considering National Guidelines. Although some of the guidance for Remote Education has been withdrawn, the Department for Education (2022) still emphasises the need for schools to be prepared to implement high-quality remote learning. There is plenty of other guidance and training available to educators and it may be important to justify the importance of this training considering the effectiveness or lack of effectiveness during previous periods of remote learning. Furthermore, there are children at the school who may benefit from remote learning in times where they are unable to attend school. For example, one child at the school suffers from an auto-immune disorder affecting her eyes and any time there is the risk of infection, she is sent home. Could this child benefit from remote learning? Perhaps remote learning could be used to support the transition of the newest children in the school. Would it be beneficial for these children to be introduced to class adults before they arrive at the school?

In Article 28 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNICEF,2009) it states that every child has the right to an education. Furthermore, the government initiative, Every Child Matters (2004) and the Children’s Act (2004) outline the educator’s responsibility to support a child in reaching their potential. We must be creative in discovering how to utilise time wisely online because lockdown and remote education is likely to remain a part of life (DofE, 2021). The DofE also recognises how the development of remote education is likely to be incorporated into in-person teaching after the pandemic and discusses how OFSTED have prioritised the understanding of successful remote education (DofE, 2021).

Methodology

Remote learning was not a planned intervention. It was a reactive intervention required to support children during a National Lockdown. Therefore, this research is retrospective. It relies heavily on data produced at the time (2021) and opinions about the time that are retrospective.

I have utilised a mixed method approach to collecting data. To some, thoughtful mixing of a methods is an effective way to provide multiple differing, connecting and complementary views (Gallagher, 2009). I will use a mixture of qualitative and quantitative data in order to answer my question which Gallagher (2009) describes as ‘robust’ data (pg.90). Quantitative data will provide me with reliability whereas qualitative data will provide me with other insights and initiate more questions.

There were several ways that engagement was tracked before, during and after the remote learning period. During the period of December 2020– March 2021, all the learning and observations were recorded on an online platform called Tapestry. On Tapestry, the Education department keeps track of both Child-initiated learning (play and exploration) and Curriculum learning (Maths, English, Reading, Science and Topic subjects like Geography and History) =. Every Tapestry entry records the learning objective, overall assessment (Green – achieved, Pink – not achieved) and how the child engaged in the learning (Mastered – Active engagement, Gaining skills – Passive engagement and Encountered – Not engaged) as well as a description of any other details or observations from the session. I will record and compare the number of curriculum subjects inputted onto Tapestry before, during and after the lockdown as well as the engagement stamp for the learning (Mastered, Gaining skills or Encountered). Collecting the data on Tapestry will allow me to have some quantitive data in order to compare the three different periods and better understand the children’s engagement with curriculum subjects.

I will also collect the views of the adults working in education at the time of the remote learning in January 2021. Collecting class adults’ responses and experiences of remote learning will give me another perspective and angle to the research question. Gallagher (2009) suggests providing research from different sources which can then be ‘triangulated’ (pg.89) which can be used to find links and congruent opinions which could validate the research.

I decided to collect the views of the class adults for several reasons. First, adults were assessing the children’s engagement before, during and after the remote learning period. It will be important to collect ideas about how they assessed engagement. Also, research has shown how strong teacher – child relationships help a child feel secure and confident, which encourages the child to become an active explorer in the learning environment (Cadima et al., 2015). In a sense, this implies that class adults and their relationships with the children also has an impact on engagement. How much do adults facilitate engagement as well and how easy is this to achieve online?

I have used a mixed questionnaire to collect data on the adult’s attitude to the remote learning that took place at this time. This included both closed and open – ended questions, which allowed me to collect both qualitative and quantitative data.

Ethical considerations…

It is my responsibility to consider and address the ethical issues involved in this project. In order to protect the identity of the children in this research and comply with GDPR as well as the school’s policy, I have changed the names of the children and classrooms in the research and have not mentioned any adults specifically by name (GDPR, 2018 and The Mulberry Bush, 2018).

The Data

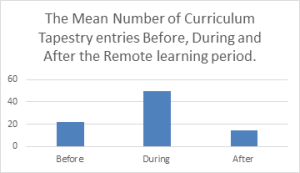

The following Bar chart shows the calculated Mean of the children’s engagement in Robin class before, during and after the remote learning period.

This bar chart shows a significant increase in both Mastered and Gaining skills engagement stamps recorded on Tapestry during the lockdown period. One explanation for this is the incredible increase in exposure to the curriculum the children received during the remote learning period.

There are just over double the number of Curriculum entries recorded during the remote learning period as there was before. Whereas there were less Curriculum Tapestry entries after the remote learning compared to both before and during.

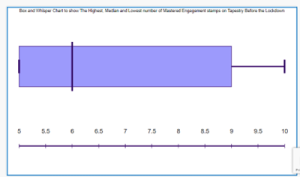

In order to look more specifically at children who engage more or less during the remote learning, I will also calculate the highest, median and lowest numbers of Mastered Curriculum Tapestry entries for the 7 children in Robin class. This will show me the bigger picture, demonstrating the range of responses to remote learning. This will also allow me to determine which children engaged the best during the remote learning period and which children did not engage as well. This will allow me to consider other environmental factors that could be affecting engagement at these times. For example, if the child is new to the school or has recently changed teachers and class.

Box and Whisper Chart to show the Highest, Median and Lowest number of Mastered Engagement stamps on Tapestry Before the Remote learning period.

Box and Whisper Chart to show the Highest, Median and Lowest number of Mastered Engagement stamps on Tapestry During the Remote Learning Period.

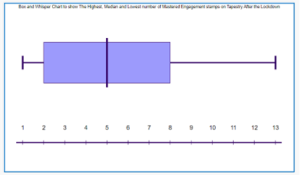

Box and Whisper Chart to show the Highest, Median and Lowest number of Mastered Engagement Stamps on Tapestry After the Remote learning period.

The Box and Whisper Charts illustrate how the highest and lowest figures affected the mean. There was quite a big range in Mastered stamps during the remote learning period compared to before and after (Before = 5, During = 17 and After = 12). This implies that there was a greater difference in engagement during the remote learning period.

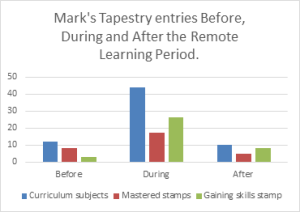

Mark was the child during the remote learning period who had the highest number of Mastered engagement stamps and had a total of 44 Curriculum Tapestry entries. John was another child who had a large number of Curriculum Tapestry entries (35) and a significant number of Mastered (4) and Gaining skills engagement stamps (31).

On the other hand, Thomas had the lowest number of Curriculum Tapestry entries during the remote learning period and the least number of Mastered engagement stamps (0) and Gaining skills stamps (6). Thomas was a massive outlier in the data during the remote learning period, only having 8 recorded Curriculum Tapestry entries and 0 Mastered Engagement stamps. This may have affected the mean calculated and shown earlier in the analysis section.

Questionnaire

I received 8 questionnaires back from class adults who were responsible for delivering remote learning. The questionnaire showed a lot about adults’ preparedness for the remote learning, as well as access to technology and competence with delivering remote learning sessions. Half of the adults didn’t feel ready for the remote learning session in 2021. A scale was used to measure the competence of adults when delivering the remote learning sessions.

5 out of the 8 class adults scored a 7/10 or above when asked to rate their competence delivering remote learning (10 being the most competent and 1 being incompetent). 2 adults scored in the middle and 1 adult scored below 5.

Furthermore, half of the adults described engagement as difficult to assess whereas, half of the adults described it as the only thing you could assess in a remote learning session. These adults also highlighted three children in particular who engaged very well: Mark, John and Drew whose name appeared on at least 2 adults’ questionnaires.

Analysis:

The data implies that some children engaged very well in the remote learning and some did not. Overall, there was an increase in Curriculum Tapestry entries, suggesting an increased exposure to the curriculum. Furthermore, adults delivering remote learning also had varied experience, with varying levels of competence, readiness and access to remote technologies. The responses about adult readiness for remote learning matches Khlaif et al., (2021) research which illustrated how ill-prepared educators were.

One important observation is in the split in results given about adults’ assessment for engagement. Adults either found engagement to be the only factor to assess in remote learning sessions or they found it impossible to assess. Some adults found engagement difficult to assess online, describing a loss of observable behaviours online that indicate engagement – body language, facial expressions, tone of voice, etc. For me engagement becomes something educators are more likely to achieve when we are attuned to individual children’s needs, interest and behaviours. Many of the children were either recently new or still new to the school (being there less than 6 months). Robin class adults don’t yet know what engagement really looks like for some of these children in-person in the classroom let alone remotely at home.

What is clear, is that the exposure to the Curriculum was not equal for all children in Robin class during the remote learning period. For some children, i.e Thomas, the school didn’t meet the expectations outlined in the Guidance for mainstream or SEND schools (Department of Education, 2022). However, for me, Thomas’ living conditions during the National Lockdown would explain his lack of access and engagement in the curriculum. First, Thomas is often dysregulated because of his traumatic early life experiences and he also has ADHD (attention deficit disorder) making it difficult for Thomas to focus on tasks for sustained periods of time. Thomas also lives in a house with many pets (who he had to introduce to class adults during remote session) and according to his background, he can be triggered by a relative who was living in the house during the National Lockdown. Thomas’ biological father would support the sessions but there was little he could do to keep Thomas on-task.

However, on the other hand, the three children who engaged best in remote learning, were all supported by adults at home. There were even times when parents and guardians would be involved in some of these lessons which was documented in some of the Tapestry entries. ‘John engaged very well in his remote maths lesson today. We used Mathsframe to combine coins to make certain amounts to buy toys in a virtual shop! Mum joined in and wanted to buy a teddy for John.’ This reminded me of some of Bowlby’s Secure Base work which describes the need for children to have a secure base to feel safe and explore freely and curiously (Bergin and Bergin, 2006). Welby (2021) emphasises the importance of parent engagement for children to have a successful remote learning experience, especially children with learning and mental health difficulties. Bergin and Bergin (2006) talk about how children will use their attachment figures to support their exploration of novel situations with the ability to return to these figures if they are threatened. Perhaps the more the children engaged in the remote learning, the stronger their attachment was to their foster families or adoptive parents.

Furthermore, the screen and separation of class adults and children meant that there was another form of safety: remoteness. Perhaps children felt safer to explore the novel situation (in this case, any learning) because it didn’t feel real. In other words, the novel learning material becomes graphics in a video game.

The fact that the number of Curriculum Tapestry entries doubled in the remote learning period suggests something about the class adults’ ability to deliver the curriculum during this time compared to in-person. In person, adults are typically met with a lot of resistance to learning tasks, especially in Robin class, the entry-level class at the Mulberry Bush School. At times, academic tasks like Maths or writing can trigger quite strong behavioural responses. Adults can also be met with powerful projections and transferences when working with these children which can burden practitioners (Pelligrini, 2010). Collie (2008) recognises the resilience and strength needed to work with traumatised children. Perhaps, safety behind the screen allowed class adults to have the resilience needed to approach these children with Curriculum subjects?

However, this leaves me questioning who was bearing the brunt of those projections? In 2022, we saw a reduction of parents and guardians wanting remote learning. During March 2022 when children were sent home more recently, 12 children out of 25 were sent home. Of those only 4 wanted remote learning. During the National lockdown in 2021 when the study observed, all of the children were either sent home or sent to the Burrow and all children at home were provided with remote learning and learning packs. Although the lockdowns happened for different lengths of time, fewer parents and guardians wanted remote learning the second time round. This meant that 8 children didn’t receive any education for 3 days. As a teacher, this doesn’t sit very well with me but it is also important to keep in mind that parents and guardians were having to manage the children’s difficult behaviour. As experienced, knowledgeable practioners working with these children, it was important for us to guide parents and work with them. Welby (2021) stresses the importance of parent and teacher involvement, collaboration and communication for a child’s success with remote learning. I’m not sure this always happened during the remote learning period.

Another reason there might have been an increase in exposure to the curriculum because it was the only type of education that was available for adults and children. In a classroom, the children also have the challenge of learning how to be a group. Nitsun (2015) describes ‘anti-group’ processes threatening the functioning of a group due to fear, anxiety and distrust of the group. These children do not trust or feel safe in groups, which Riva and Korinec (2004) identify as key elements for participation in groups. Also, it takes a certain level of skill to navigate social situations and these children have lacked parental figures who effectively modelled this for them in the past. Children online, did not have to contend with these challenges and so had more of a capacity and tolerance to access their curriculum learning.

Evaluation

This research has reiterated the importance of safety when learning. Perry and Szlavitz (2006) describe the educational system as disrespecting the importance of relationships in school. This research confirms the importance of safety in relationships for children to engage with their learning in Robin class. Children who were sent home in 2021 and engaged with the remote learning, had parents and guardians who were present and involved in their learning at home. Whereas, children who had many distractions and triggering relationships with their families, engaged less. I can use these ideas in my day-to-day work with the children, remembering that relationships are key and children (and people) work best with fewer distractions.

Assessing engagement became somewhat problematic for the class adults delivering remote learning. Half of the adults found this difficult and the other half said it was the only thing to assess. In fact, a large portion of data was missing from this research because class adults in 2021 did not track what is referred to as ‘On-track’ in the department. On-track tracks a child’s level of engagement in learning related behaviours (I can settle into a classroom; I can wait for an adult to explain things; I can end one thing and then start the next calmly). This data was not tracked for the remote learning period in January 2021. Juuti (2021) discusses the difficulty teachers have assessing ‘level of interest’ even in a classroom and during remote learning, the teacher will have less information about the children’s feelings and thoughts about their learning. This leaves me asking more questions about engagement and the observable behaviours of engagement. How can we do this accurately online? How does this compare to in-person? Assessing engagement feels complex and perhaps we as a department need to collaborate on our assessment of engagement, ensuring that it is more standardised, especially during Remote learning periods.

Finally, this research has also confirmed for me how engaging technology can be for children. Bond and Bedenlier (2019) discuss how providing opportunities to access technology can increase children’s sense of community, motivation, interest in learning and self-regulation which are all components of engagement (Khlaif et al., 2021). Therefore, I have taken this information into the Mulberry Bush’s IT steering group meetings and used it as a way to incentivize the organisation’s aim of making the technology at the Mulberry Bush Cutting Edge.

This research has raised more questions and hasn’t fully addressed my question. For a number of reasons, the gaps in the data make it very difficult to fully answer this question. Khlaif et al., (2021) describe educators experiencing a large intensity of stress, uncertainty and anxiety during the remote learning period and were not well prepared for the transition. This resonates strongly and may explain the gaps and inconsistencies in the data. However, there were other factors that may have affected my data. In addition to remote learning, many other variables may have affected engagement in Curriculum subjects before, during and after the remote learning period. These included: a World pandemic and National lockdown; a change of teacher (3 out of the 6 children moved class after the lockdown); 2 children were new to the school and had only been there for a month before they were sent home; the transitions to and from home and school; school holidays (Christmas and Half Term).

I was very fortunate with my research to have a lot of the data already available to me in the form of Tapestry. Not all schools and organisations record engagement as we do at the Mulberry Bush. However, the difficulty was that we didn’t always collaborate on what engagement looks like online. In fact, half of the adults in the questionnaire commented on how difficult it had been to assess engagement remotely. One adult even said that she wasn’t always certain that her student was looking at the right screen. It is difficult to distinguish the observable behaviours on the screen that would indicate engagement.

There were several other limiting factors to my research project. I will reiterate the limitation of the time in which the research took place. Three 2 week intervals is a short period of time to collect data. These weeks also fell on 2 school holidays which has a tendency to trigger difficult behavioural responses with our children who can find transitions difficult. For me, the short duration of the remote learning period also forces me to question how much the novelty of remote learning played a part in the engagement.

Lastly, this is an incredibly small sample size to validate the research and it would need to be replicated (but hopefully not under the same conditions). According to Gallagher (2009) it is important to have multiple perspectives to make research more reliable. For example, it would be very interesting to include both the children’s and the parent’s view about the remote learning. This could be done in future research.

This research has confirmed the importance of collaboration which would be a recommendation I’d give other practitioners for approaching remote learning. All of the adults completing the questionnaire said they were well supported during the remote learning period. Support took the form of regular debriefs with team members and sharing resources. This decreased the levels of isolation with the task of remote learning and allowed education adults to develop their skills and practice. The quality of remote learning developed over time, progressing from adults filming themselves teaching a class, to adults facilitating group discussions and break-out rooms on Zoom.

Collaboration shouldn’t be limited to adults working in the organisation but should also be extended to parents and guardians. I do not feel this happened very well in the previous lockdowns which is reiterated in other research about remote learning (Khlaif et al., 2021). This research has shown the importance of collaboration with parents and guardians at home. Ansong et al., (2017) discusses the importance of parents motivating their children and how this has a positive impact on engagement. Parents, in a sense, become the cheerleaders. Mulberry Bush School children may never have experienced this and so, the remote learning provided a brilliant opportunity for parents and educators to collaborate in order to cheerlead effectively, provide containment and safety for these children so they could engage with their learning.

A final recommendation I would make to practitioners both in-person and remotely, would be the Importance of meeting the child where they are? In many of the observations recorded on Tapestry during the Remote learning period in 2021, was the children’s enjoyment in showing class adults around their house, introducing them to family pets and showing their favourite toys. This, in itself, acted as an excellent material in order to inspire engagement.

Ariel Lambert, 2022

Reference list:

Ansong, D., Okumu, M., Bowen, G. L., Walker, A. M., & Eisensmith, S. R. (2017) The role of parent, classmate, and teacher support in student engagement: Evidence from Ghana. International Journal of Educational Development, [online]. 54, pp. 51–58. [Accessed 15th April 2022].

Becker, S. P., Breaux, R., Cusick, C. N., Dvorsky, M. R., Marsh, N. P., Sciberras, E., & Langberg, J. M. (2020) Remote learning during COVID-19: Examining school practices, service continuation, and difficulties for adolescents with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Adolescent Health [online]. 67(6), pp. 769–777. [Accessed 10th May 2022].

Bergin, C. & Bergin, D. (2009) Attachment in the Classroom. Educational psychology review [online]. 21(2), pp. 141-170. [Accessed 13th April 2022].

Bion, W.R. (1969) Cogitations [online]. London: Karnac.[Accessed 1st May 2022].

Bond, M. & Bedenlier, S. (2019) Facilitating student engagement through educational technology: Towards a conceptual framework. Journal of Interactive Media in Education [online]. 11, pp.1-14. [Accessed 20th April 2022].

Cadima J., Doumen S., Verschueren K., Buyse E., (2015) Child engagement in the transition to school: Contributions of self – regulation, teacher-child relationships and classroom climate. Early Childhood Research Quarterly [online]. 32, pp1-12. [Accessed 25th April 2022].

Chzhen, Y., Symonds, J., Devine, D., Mikolai, J., Harkness, S., Sloan, Seaneen, S., and Sainz, GM., (2022) Learning in a Pandemic: Primary School children’s Emotional Engagement with Remote Schooling during the spring 2020 Covid-19 Lockdown in Ireland. Child Ind Res [online] [Accessed 21 April 2022].

Collie, A. (2008) Consciously working at the unconscious level: Psychodynamic theory in action in a training environment. Journal of Social Work Practice [online]. 22(3) pp 345 – 358 [accessed 23 March 2021].

Gallagher J., (2009) Data Collection and Analysis. In Tisdall, K., Davies J.M., and Gallagherm J., ed. (2009) Researching with Children and young people: Research, Design Methods and Analysis [online]. London: Sage, pp 89-113. [Accessed 25th April 2022].

General Protect Data Regulation (GPDR) (2018) Available from: https://gdpr-info.eu [Accessed 24th April].

Her Majesty’s Government, (2004). Children Act 2004 London: Her Majesty’s stationery office. Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2004/31/contents (Accessed: 21 May 2021).

JUUTI, K., 2021. Primary Students’ Experiences of Remote Learning during COVID-19 School Closures: A Case Study of Finland. Education Sciences [online]. 11(9), pp. 560. [Accessed 15th April 2022].

Khlaif, Z.N., Salha, S. & Kouraichi, B. (2021) Emergency remote learning during COVID-19 crisis: Students’ engagement. Educ Inf Technol [online]. 26, pp 7033–7055. [Accessed 5th May 2022].

Lee J-S., (2012) The effects of the teacher–student relationship and academic press on student engagement and academic performance, International Journal of Educational Research, [online]. 53, pp. 330-340. [Accessed 15th April 2022].

McLeod, S. A. (2017) Bowlby’s attachment theory. Available from: www.simplypsychology.org/bowlby.html [Accessed 13th April 2022].

Nitsun, M. (2015) Beyond the Anti-Group : Survival and Transformation [online] London: Routledge [Accessed 25th April 2022].

Pellegrini , D. W. (2010) Splitting and projection: drawing on psychodynamics in educational psychology practice. Educational Psychology in Practice [online]. 26(3), pp 251-260. [Accessed 24 March 2021].

Perry, B., and Szalavitz M., (2006), The boy who was raised as a dog: and other stories from a child psychiatrist’s notebook : what traumatized children can teach us about loss, love, and healing. New York: Basic Books.

Riva, M. T. and Korinek, L. (2004) Teaching Group Work: Modeling Group Leader and Member Behaviors in the Classroom to Demonstrate Group Theory, The Journal for Specialists in Group Work [online] 29(1), pp55-63. [accessed 20 April 2022].

The Department for Education, (2004). Every Child Matters. [Online]. London: Department for Education. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/272064/5860.pdf [Accessed 2nd May 2022].

The Department for Education, (2015) Keeping Children Safe in Education. [Online].

London: DfE Available from:https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/keeping-children-safe-in-education–2 [Accessed on 22 April 2022].

The Department for Education, (2020) Providing Remote Education: Guidance for schools, [Online]. London: DfE Available from:https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/providing-remote-education-guidance-for-schools/providing-remote-education-guidance-for-schools [Accessed: 6th May 2022].

The Department of Education, (2022) Statutory expectations and obligations. [Online]. London: DfE Available from: https://get-help-with-remote-education.education.gov.uk/statutory-obligations.html [Accessed 4th May 2022].

UNESCO (2021) COVID 19 [online] https://en.unesco.org/news/137-billion-students-now-home-covid-19-school-closures-expand-ministers-scale-multimedia [Accessed 10th May 2022].

UNICEF (2009) The UN convention on the rights of the child [online] London: Unicef UK, Available from: https://www.unicef.org.uk/what-we-do/un-convention-child-rights/ [Accessed 20 April 2022].

Veiga FH, Festas I, Taveira C, Galvão D, Janeiro I, Conboy J, Nogueira J. (2012) Student’s engagement in school: concept and relationship with academic performance—its importance in teacher training. Revista Portuguesa de Pedagogia [online]. 46(2) pp. 31–47. [Accessed 3rd May 2022].

The Mulberry Bush (2018) The Data Protection Policy [Accessed online] https://mulberrybush.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/The-Mulberry-Bush-GDPR101-Data-Protection-Policy-Sept-2018-1.pdf [Accessed 12th May 2022].

Tualaulelei, E., Burke, K., Fanshawe, M., & Cameron, C. (2021). Mapping pedagogical touchpoints: Exploring online student engagement and course design. Active Learning in Higher Education [online]. [Accessed 24th April 2022]

Welby, K.A., (2021) Remote Learning Strategies for Students with IEPs

An Educator’s Guidebook [online]. London: Routledge. [Accessed 10th May 2022].