James Havey, Glenn Miles, Lim Vanntheary, Nhanh Chantha, Ou Sopheara, Sreang Phaly and Eliza Piano

Preface

The next four journals will be exploring lessons learned from the Butterfly Longitudinal Research Project (BLRP). This 10-year research project followed the lives of 128 survivors of human trafficking, exploitation and abuse in Cambodia as they received aftercare services from NGOs and re/integrated back into the community. This project was implemented in conjunction with NGOs and wider stakeholders who helped in the development and implementation of its policy, findings and recommendations.

This article is introducing the BLRP while the subsequent three papers will cover; 1) the experiences of participants of vulnerability and resilience, 2) spiritual journeys of survivors, and 3) survivor-voiced recommendations to a diversity of stakeholders about how they can be better supported.

The Research team over the past ten years were:

- Orng Long Heng, 2010 – 2013

- Heang Sophal, 2011- 2014

- Lim Vanntheary, 2011-2019 (Project Manager)

- Dane So, 2012-2013 & 2020

- Sreang Phaly, 2013-2020 (Project Administrator)

- Nhanh Channtha, 2014-2019 (Assistant Project Manager)

- Bun Davin, 2015-2017

- Phoeuk Phellen, 2015-2019

- Ou Sopheara, 2016-2019 (Assistant Project Manager)

- Kang Chimey, 2017-2019

- Siobhan Miles, 2009-2016 (Supervisor) (RIP)

- James Havey, 2017-2020 (Supervisor)

We dedicate this series of papers to Siobhan Miles who died suddenly and unexpectedly in 2016.

Introduction

The Butterfly Longitudinal Research Project (BLRP) was founded by the Chab Dai Coalition, a group of primarily faith-based non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in Cambodia. The idea of the BLRP formulated in 2009 when Helen Sworn, the founder of Chab Dai, Siobhan Miles, project manager of the BLRP, and Glenn Miles, PhD, its academic advisor, along with other stakeholders and practitioners in Phnom Penh’s anti-trafficking community were debriefing the Reimer et al. (2007) study, The Road Home: Toward a model of ‘reintegration’ and considerations for alternative care for children trafficked for sexual exploitation in Cambodia. Following this discussion and beginning in 2010, the BLRP commenced. Since then, the BLRP has been following the lives of 128 child and adult survivors of human trafficking, exploitation, and/or abuse. From 2010 through 2019, this study sought to find out if freedom from their exploitative history was truly free and what are the factors to its (non-) sustainability.

This collaborative research among NGOs – with a purposeful focus on the needs of NGOs rather than academia – has attempted to understand the positive and negative aspects of aftercare in order to improve these services and make the re/integration of trafficking survivors back into communities as smooth as possible.

Since its inception, the BLRP has chosen to take grants from smaller, locally-involved grant bodies rather than larger academic institutions in order to actively concentrate on the grassroots, survivor-facing NGOs. The BLRP is grateful to ACCI, Change a Path, Imago Dei Fund, Karakin Foundation, Love 146, Stronger Together, Tenth Church, and all of the anonymous donors for their continued financial support. These organizations and the people in them have shared in our foundational belief that knowledge and survivor voices are essential for a brighter future free of human trafficking.

The BLRP is also grateful to all the Assistant Programmes (APs) who assisted in making this research possible. The APs were instrumental in: recruitment of study participants; giving the project feedback on what topics they would find helpful throughout the decade of study; and, participating in the presentation and dialogue of the research’s findings and recommendations. The BLRP would not be as relevant and impactful without these organizations’ commitment to listening to survivors to shape programs and policy. Agape International Mission (AIM), American Rehabilitation Ministries (ARM), Bloom Asia, Cambodian Hope Organization (CHO), Citipointe International Care and Aids, Daughters of Cambodia, Destiny Rescue, Garden of Hope in Cambodia, Hagar Cambodia, Health Care Centre for Children (HCC), Hope for Justice, International Justice Mission (IJM), Pleroma Home for Girls, Ratanak International, World Hope, & World Vision.

Methodology

While always longitudinal in nature, the BLRP has taken a mixed methodology approach in its data collection and reporting. This has allowed for a diversity of ways a respondent could volunteer their story to the research team. Qualitative in-depth interviews and longitudinal quantitative surveying has also developed a deep sense of trust between the researcher and participant as various subjects were investigated and reflected upon during the interviews. More specifically, the BLRP is a prospective panel longitudinal research, designed to interview the same 128 survivors of human trafficking, exploitation, and/or abuse over the course of the 10-year project—a world’s first of its kind (Babbie, 2007; Bryman, 2008; Menard, 2002).

Due to the ever-changing nature of the survivors’ situations and the needs of the aftercare community, including changes in government policy, the methodology and approach of the BLRP had to adapt throughout the decade. From 2011-2013 there was a heavy focus on quantitative data collection and annual reporting that covered a large variety of all themes asked about throughout the year. During this time, many participants were still involved with, or newly out of, residential aftercare shelters for human trafficking survivors, resulting in reliable access to each participant for frequent data collection and surveying.

However, many factors resulted in a methodology shift in 2014. Firstly, there was better rapport being built between the researcher and participants that allowed for the participants to feel comfortable sharing their experiences in more detail than what the restrictive quantitative survey allowed for. In response, the team began to use qualitative In-depth Interview (IDI) survey tools that consisted primarily of open-ended questions. This shift was also in response to many participants being adults and able to discuss their experiences and feelings more thoroughly.

Recruitment of Participants

The BLRP research team worked to develop trustworthy and long-lasting relationships with the survivor-participants and their families in order to minimize attrition over the years of the project; throughout their stay within aftercare shelters, re/integration back into the communities and beyond as their service completed. The participants were recruited through 14 aftercare programmes for young women, girls and boys, aged 12-30 years.

Retention was challenging in the early years, with some participants leaving the country, losing their phones, changing addresses, or being otherwise unreachable due to various circumstances outside of either the survivors’ or the NGO control. Some survivors were unwilling to continue to meet with staff due to questions being asked by community and family members about why researchers were meeting them which they were afraid would lead to stigma. However, the majority of survivors did stay in touch, allowing the BLRP team to track the outcomes of aftercare. Due to the efforts made by the staff to build trust and communication with the survivors, in 2018 – nearly a decade after the beginning of the program – 71% of survivors were still willingly participating in the research. While this has been a complicated process that has required continuous effort from the research team and participants, it has made the research richer and more detailed.

BLRP Ethical Framework

Due to the continued vulnerability among survivor-participants, the BLRP adhered to a strict ethical research framework so as to, ‘do no harm’ (Bryant & Landman, 2020; Zimmerman & Watts, 2003; CP MERG, 2012; Ennew & Plateau, 2004; Robin & Rachan, 2019, p. 12; Taylor & Latonero, 2018; UNIAP, 2008). This echoed guidelines and frameworks set forth by academic institutions experienced in working with survivors of human trafficking, exploitation and sexual abuse. It is hoped that by communicating these in detail, future studies seeking to replicate the BLRP may use these as a framework for developing their own.

The BLRP sought approval by the National Ethics Committee of the Royal Government of Cambodia, Ministry of Health (NEC). In doing so, this built legitimacy and trust of the study’s activities among its participants and their families, audiences, policymakers and donors. It was necessary to secure protection of team members and the Chab Dai Coalition as they handled legally sensitive data.

The participants of the BLRP understood well about how their continued participation in this study was voluntary as their written consent was given annually and verbal consent was asked and recorded before every interview was conducted (Marshall et al., 2014). Finally, there was no monetary compensation given to the participants for their involvement in the study.

The BLRP also provided referral services for its participants when the need arose. Respondents were able to call a project phone number day or night to speak with a team member and if any needs were discussed during the conversation, the researcher would subsequently seek interventions for participants among partner NGOs (Taylor & Latonero, 2018, p. 12).

The BLRP researchers committed to strict parameters surrounding: photos, media, data management, and interviews. Furthermore, all participants’ identities were only known by the Cambodian research team (Taylor & Latonero, 2018). Pictures of participants were not taken in order to create a space where the participants feel safe and comfortable answering interview questions; promoting the participant’s individual dignity and rights to privacy (Zimmerman & Watts, 2003). Furthermore, only the BLRP team members and contracted consultants were allowed access to the study’s data throughout the years and specific measures were taken to ensure that neither the physical nor digital stores were lost.

One unique consideration of the BLRPs confidentiality protocols was the need for a trusted driver of the project. Many of the interviews for the study took place at the participants’ homes, so the driver needed to uphold the project’s standards of confidentiality when transporting researchers to interview locations.

Key Findings

After 9 years of studying and 4,500+ files of data collected, while in preparation for the final report and closing of the BLRP, the team developed an illustrated report of what were found to be the study’s top 10 findings, thus far (Havey et al., 2018). These findings run the gamut of all the thematic topics survivors were interviewed about in the research leading up to its final year of data collection including, but not limited to: the importance of survivor-voiced research and ethical storytelling; issues specifically pertaining to the aftercare of male survivors; multi-faceted needs while working with families of trafficking survivors not just the survivors themselves; standards in shelter care and vocational training; and, the role spirituality plays in a survivor’s recovery journey. These ‘Top 10’ are to be seen as an overview of findings from this research, not the recommendations for actions stakeholders to take. Recommendations – along with deep dives through themes – will be explored further in the subsequent articles.

As mentioned previously, the research topics were driven primarily by the requests of the NGO community. There has been a continuous sharing of information over the years with the APs of the BLRP and other stakeholders in the care of trafficking survivors in order to ensure that the findings and recommendations of the BLRP result in action. Communication has been done through round table meetings with partner organisations and in national, regional and international conferences. Technical reports were also produced and made available through the Chab Dai website. In recent years, the data has been analysed by academic researchers and published in peer review journals.

The deep trust the participants have built towards the research team has led to richer and more authentic interviews over the years.

“…the team believe retention is largely due to participants trusting that their identities will be kept confidential, their stories matter and they are valued as individuals.”

Miles, Heang, Lim, Nhanh, Sreang. (2014). Butterfly Methodology Change: A Reflection Paper, “Longitudinal research design and methodology”. p4.

“During regular interviews, the BLR team conducts individualized and confidential meeting, with active and attentive listening as the primary goal. The research team strives to provide a safe space, in which the boy’s thoughts and emotions can be validated as real and important. This kind of space seems to be starkly contrasted to the king of environment that many of the male cohort live in from day-to-day. For a number of respondents, their interviews seem to be a much-needed space where they are able to express pent-up emotions—something that seems to be especially true as time progresses through the re/integration process [and beyond].”

Davis, Havey, Lim, Nhanh, Sreang. (2016). The Forgotten Cohort. p25.

“There are many children who like this [participating in the BLR interviews] besides even me, personally I like it very much because we have a lot of chances to say/share what we never tell others. But when I meet with you, I can tell you and you not only listen to me, but you also bring my idea to practice. That is what I think and I am really thankful for this.” (Dary, female, 2016)

Cordisco-Tsai, Lim, Nahn. (2018). Experiences in Shelter Care, “Recommendation #1: Listen to clients and be receptive to their input. Ask for their ideas and Act on them”.

The shelters for the male participants ended up being highly emotionally and physically violent for a number of reasons, including: bullying, xenophobia, and elitism.

One respondent gave a recommendation that boys in the shelters need to be separated along age and maturity lines, because the physical, mental, and sexual maturation is severely different between 12 and 16 year-old males.

“…At first, staying there [at the shelter for abused boys] was easy because we were the same age and we respected each other…It [trouble] started after the big boys came.” (Panya, male, 2015)

Cordisco-Tsai, Lim, Nahn. (2018). Experiences in Shelter Care, “Recommendation #15: Separate boys into smaller groups [in a shelter program] to protect the vulnerable”.

Davis, Havey, Lim, Nhanh, Sreang. (2016). The Forgotten Cohort: An Exploration of Themes and Patterns Among Male Survivors of Sexual Exploitation & Trafficking.

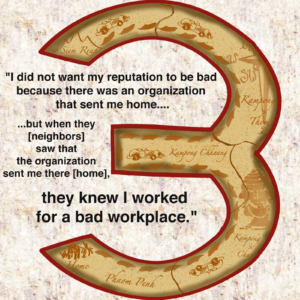

On top of the stigma against this cohort within a community, NGOs and shelters have unintentionally created a stigma against the children and youth they work with.

This being that because of these respondents’ association with the NGOs and living at the shelters for years on end, the community they have been re/integrated into sees them as being promiscuous.

“Friends at school made me feel unhappy because they mocked me and say bad words about me. I felt they were discriminating against me because they know that I used to live in a shelter. They say that shelter children were sexually exploited and raped until they got pregnant without a husband.” (female, Age 13, 2012)

Morrison, Miles, Schafer, Heang, Lim, Sreang, Nhanh. (2014). Resilience: Survivor Experiences and Expressions, “Discrimination”. p34.

“They [family] stopped looking down badly like they did before; just sometimes they recall my bad background, which then hurts my feelings, when my sister blames me for going out at night…but in my mind I’m afraid of my brother-in-law who looks down on me, even now… He blames me and looks down on me most of the time. Whenever he has a problem with my sister he blames me for being a prostitute and calls our family ‘prostitute family’.” (female, 2012)

Morrison, Miles, Lim, Nhanh, Sreang, Bun. (2015). Survivor Experiences and Perceptions of Stigma, “Persistence of Stigma among survivors: Continual Reminders”. p31.

“I did not want my reputation to be bad because there was an organization that sent me home. The word organization – they had to help and what was I that was wrong? They said they brought me to my home, so my neighbours would ask what I was that was wrong and why there was an organization that sent me there… I felt embarrassed. Although I was fatherless and I was poor, so when I went to live in the organization, they also did not believe me…. They [neighbours] do not speak ill about me, but when they saw that the organization sent me there, they knew I worked for a bad workplace.” (Da, female, 2016)

Cordisco-Tsai, Lim, Nahn. (2018). Experiences in Shelter Care, “Findings: Case Study of Participants in a Shelter for Adult Women: Limited follow-up and lack of interest in contacting shelter staff in community”.

There is a real sense of ‘shock’ once a participant is re/integrated back into the community from a shelter because of the realities of struggles their family has on a daily basis that is not true while living with the NGO (i.e. money for food, stable housing, stable education and skills training, etc.).

Once this shock is relieved and some semblance of stability was observed by the NGO, their case is closed and access to the wealth of resources the NGO provides is cut-off. This has led participants wondering why they were treated like family within the shelter but then feeling ‘dropped’ back in the community.

Moreover, participants have responded to these experiences by:

- feeling socially isolated from the culture and spirituality of their re/integrating communities (especially because all but one associating partner NGOs in this study were Christian), and

- feeling like promises made by the shelter have been unfulfilled (i.e. being promised that their education would be supported through their finishing of Grade 12, but once their case was closed by the NGO, the support stopped.)

“When I left the shelter, I have no chance to believe in God. I cannot go to the church.” (Female, Shelter Reintegration Assistance Follow-up, 2012)

“Before I was a Christian but now I am a Buddhist. My father pressured me to burn the incense and hasn’t allowed me to go to the church.” (Female, Shelter Reintegration Assistance Follow-up, 2012)

Miles, Heang, Lim. (2012). End of Year Progress Report 2012. “Spirituality & Religion”. p110.

“A strong majority of [BLR male] respondents (79%) cite feeling the effects of poverty in a variety of ways as they are re/integrated back to their communities. Among the 79%, one-in- five describe lacking food, nearly half (47%) cite having insufficient education for gainful employment, and nearly a third (32%) cite an inability to live with their immediate families due to poverty.”

Davis, Havey, Lim, Nhanh, Sreang. (2016). The Forgotten Cohort. p14.

“All organizations, if they help the children, please help them to become successful and do not abandon them. In addition, please do not think that those children who have a job and can stand strong, that is not right. On the other hand, they have to visit them or their family to know the reality of their situation… They have to follow up with them often and use polite and sweet words to them.” (Dary, female, 2015)

Cordisco-Tsai, Lim, Nahn. (2018). Experiences in Shelter Care, “Recommendation 17: Phase out support more incrementally”.

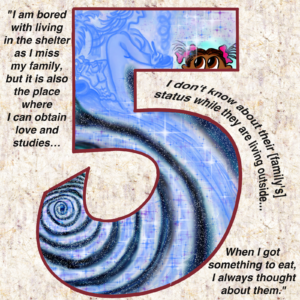

There is a heavy lack of the NGOs working with the families of the participants while in the shelter, before re/integration, and during re/integration.

This has left the participants:

- feeling undeserving of all these services given to them while in the shelter and wishing their family could have access to the same, or they wanted to move back home out of a semblance of solidarity with their families;

- not working with the family before the re/integration process led that aforementioned shock of re/integration back into the family and a continuing uphill battle of stable livelihood during and after the re/integration process; and

- though most of the shelters provided money for the respondents to attend school, many participants were forced to quit school to work shortly after they were re/integrated to provide financial support for their family.

“[I] act as a princess. I do not do anything [at the shelter]. After eating, I just sleep. It is easy for me and it is not like other places where people need to work hard and do not have enough food to eat.” (Sim, female, 2016)

Cordisco-Tsai, Lim, Nahn. (2018). Experiences in Shelter Care, “Feeling privileged to live in the shelter”.

“Others expressed that while they appreciated all of the benefits they obtained from living in the shelter, they worried about the wellbeing of their family members who did not have access to all the resources that the clients themselves had access to within the shelter. Vanna said:

‘I am bored with living in the Shelter as I miss my family, but it is also the place where I can obtain love and studies… I think it is easier to stay home, but I can eat enough in the shelter center. I do not know about their [family’s] status while they are living outside… When I got something to eat, I always thought about them.’” (Vanna, female, 2016)

Cordisco-Tsai, Lim, Nahn. (2018). Experiences in Shelter Care, “Limited engagement with family while in the shelter”.

“Some participants who reintegrated in 2012 described their frustration and stress at the lack of assessment and financial support in their reintegration packages, which then meant they found it difficult to stay in school or training upon leaving the shelter. They often found themselves in the same impoverished circumstances they were in prior to their sexual exploitation, and the ongoing education of participants was found to be often compromised during the reintegration process.

‘The reintegration assistance support is not enough. Twenty USD a month and a bicycle is not enough money for me to continue studying. The shelter social workers only come for less than ten minutes every few months so they do not know my difficulty.’” (Female, 2012)

Miles, Heang, Lim. (2012). End of Year Progress Report 2012, “Challenges and Barriers to Education and Training”. p89.

“Familial poverty seems to drive the majority of these [difficulties in work and school], pressuring boys to quite school and pursue ways of generating income to support their family’s basic needs. For instance, a respondent cites that his grandfather forced him to stop his studies in order to take up vocational training with his uncle. He describes that his grandfather does not believe in the importance of finishing school and prefers to that he takes up vocational training, which can earn money faster…

‘I stopped my schooling because I had no support for my studies from [the shelter NGO] anymore. So, I need to learn repairing skill with my uncle, even though I don’t like it.’”

Davis, Havey, Lim, Nhanh, Sreang. (2016). The Forgotten Cohort. p17-18.

Due to a lack of proper re/integration protocols, oversight in the stabilization of the family, and limited community resources, the participants have been forced to ‘move where the opportunities are’—this being in or out of country, multiple times a year, and/or without proper social support, increasing their vulnerability to re-exploitation.

“Almost no participant describes staying with the same family unit over three or four years. The following story by one survivor in 2013 exemplifies the blending and changing nature of her family unit during one year:

‘I live with my stepmother, father, and older sister. My stepmother and I don’t get along together. She is always making conflicts and arguing with me. My father got in a traffic accident and injured his hand. I will go to live with my real mother in the province because she called and asked me to live there.

I want to move out with my cousin. Some of my neighbours are very [rude] towards my family. They yelled at my little siblings and hit my Aunt.

I moved to live in a rental room with my older sister and cousin. I wanted to earn money to help my older sister support us because she was the only one working. I tried working in a nightclub but quit because it was not a good job. I could find other work.

I moved back to live with my father, he asked me to come back home. My father didn’t want me to live alone. My older sister married and moved out to live with her husband. I still don’t get along with my stepmother.’” (Female, 2013)

Morrison, Miles, Schafer, Heang, Lim, Sreang, Nhanh. (2014). Resilience: Survivor Experiences and Expressions, “4.2 Relationships”. p25.

“The majority of male cohort [68%] demonstrates significant housing instabilities during their re/integration periods. These instabilities seem to come from a number of factors they are faced with upon re-entering their communities. Among this majority, nearly a third (32%) of the respondents state that they had to move from their home communities to search for work. Twenty-six percent cite having to change where they lived due to violence at home or in their communities. Other reasons for housing instability include: migration to avoid an exploiter who still lived in the community, international migration of a parent, migration due to a parent’s incarceration and/or release from prison, and migration for education”

Davis, Havey, Lim, Nhanh, Sreang. (2016). The Forgotten Cohort. P18.

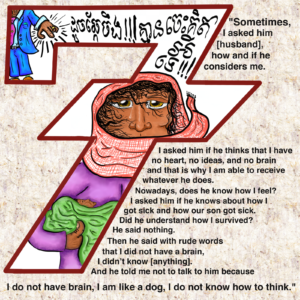

Furthermore, because of limited re/integration protocols and inattentive social workers, the participants don’t have access to the social capital to overcome compounding traumas after their ‘case has been closed’ (i.e. poverty struggles, violence in community, death of loved ones, etc.).

The Butterfly researchers have heard many respondents say to them that they are willing to meet with the team over the years, because they are the only people who will actively and confidentially listen to their stories and emotions.

“Sometimes I asked him [husband] how and if he considers me. I asked him if he thinks that I have no heart, no ideas, and no brain and that is why I am able to receive whatever he does. Nowadays, does he know how I feel? I asked him if he knows about how I got sick and how our son got sick. Did he understand how I survived? He said nothing. Then he said with rude words that I did not have a brain, I didn’t know [anything]. And he told me not to talk to him because I do not have a brain, I am like a dog, I do not know how to think.”

Morrison, Miles, Lim, Nhanh, Sreang, Bun. (2015). Survivor Experiences and Perceptions of Stigma, “Loss of Opportunities in Education”. p34.

“I am happy to see and talk to you because even [NGO] who works based in my community, they had never come to visit and ask me like you do. I am happy. It seems like they don’t care about us anymore after my case was closed. They don’t care what I am doing right now.” (Chivy, female, 2016)

Cordisco-Tsai, Lim, Nahn. (2018). Experiences in Shelter Care, “Varied experiences with case closure”.

“While no specific or diagnostic questions on emotional health were asked during interviews, it is nevertheless notable that nearly half of the male respondents seem to demonstrate a decline in emotional health as time progresses. This trend appears to be diverse and manifests in a variety of ways, including: low self-esteem, severe anxiety, anger/combativeness at home and work, isolation from family and/or peers, and suicidal thoughts…

‘We are in debt… I feel sad about this matter so much! Sometime I want to commit suicide by taking poison pills!’”

Davis, Havey, Lim, Nhanh, Sreang. (2016). The Forgotten Cohort, “Life Beyond: Poor Emotional Health”. p22-23.

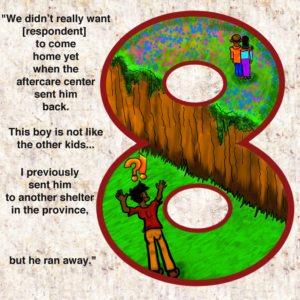

It has also come to light that the mothers and families of many participants who have been re/integrated back into the communities, deeply seek for them to be taken back by the NGO shelter program.

While with an NGO, the families then know that their children are given the care and resources they cannot provide due to the instability of their livelihoods. However noble the intentions are on part of the families, these sentiments of wanting an NGO to raise their children have left the participants feeling unwanted at home.

“This non-acceptance for a boy’s re/integration came in various forms from case-to-case. An 18-year-old respondent cited confusion when his mother did not want him to come home from the aftercare facility. While the respondent’s parents initially said that they were unable to accept the child back due to their poverty, further information from the respondent’s step-father indicates a different reason. In 2015, the research team had a conversation with the respondent’s stepfather who says, ‘we didn’t really want [this respondent] to come home yet when the aftercare center sent him back. This boy is not like the other kids.’ The stepfather cites that this participant would often leave home with peers who seemed to have a negative influence over him. The stepfather continues, ‘I previously sent him to another shelter in [the] province [for vocational training], but he ran away.’ The research team cites that his parents did not seem to care greatly for their son’s well-being. When he was eventually re/integrated back into his family, he was accepted with reluctance, as the family had no other choices for alternative care.”

Davis, Havey, Lim, Nhanh, Sreang. (2016). The Forgotten Cohort, “Reintegration: Violence from Families and/or Caretakers”. p16.

As of 2017, 23 out of 64 female participants who had stayed in a shelter program and then subsequently re/integrated back into the community have been, or are currently, in re-exploitative situations (sexually or for labour).

“Of the seven participants who responded they had been sexually active with more than one partner in the past year…four participants said they had been paid for sex…three [of these participants] said they, ‘felt they had been sexually exploited’…

‘The broker who finds clients for me takes some of my money when I have sex with the clients.’ (In-depth Interview, Female, 2011, Declined NGO Assistance)

‘My boss took half of my earnings after I had sex with the client.’ (In-depth Interview, Female, 2011, Declined NGO Assistance)

‘My boss forced me to have sex with the clients.’ (In-depth Interview, Female, 2011, Declined NGO Assistance)”

Miles, G & Miles S.et. al. (2011). End of Year Progress Report 2011, “Perspectives about Sexual Exploitation”. p105.

“Two years earlier, when the participant turned 18 years old, she told the research team that she left the shelter and went to live at a KTV establishment in another town because she needed to help her sister with her new-born baby. During that time, the research team was able to visit the participant at the KTV. Over the course of the past two years, it has appeared to the team and to the former AP that the boss has increasingly limited the participant’s freedoms and agency. He forbade her to leave the premises and took away her phone. Throughout this time, the former AP and the Butterfly Research team continued to maintain contact. Though the AP offered to help her leave, she refused to go.

Early in 2013, the participant disclosed to the Butterfly team the ‘real reason’ she returned to [the Karaoke TV establishment] was for sex work. She stated she was deeply disappointed with the shelter’s re/integration financial support. When she learned from a friend about the money she could earn in Karaoke she followed. Later this past year, the team learned from the former AP, the participant had ‘escaped’ for a few hours and had asked for their help to get free. By the time the AP were able to locate her at the police station, she had changed her mind. The AP felt the KTV owner and the police were colluding to keep her at the venue. Since that time, the owner has forbidden her to have any contact with the Butterfly Research team or the former AP.”

Miles S, Heang, Lim, Sreang, Dane. (2013). End of Year Progress Report 2013, “Vignettes About Participants Involved in Sex Work During 2013”. p67.

Out of the 20 interviews done in February 2018, the Butterfly research team has assessed that only five participants have stable livelihoods (healthy social support, stable & enough income, safe living environments, etc.). To all of the participants, when asked what their definition of a ‘successful life’ is, there has been a major focus on stable and good income.

“I don’t even know what they should do as the leaders don’t even know what they should do too…To me, I think that if they want to provide skills for women, they should allow us to study for the whole day. Please don’t ask us to learn how to sew bags for half-day and salon half-day. Time is quite short in a half-day, as we just sit there, the time is over…To make the skill helpful, they should focus on the training skills and conduct specific training. They should provide certificates to the participants to make it easier for them when they open the shop. Participants should finish their course with good training skills no matter what they learn…I think outside [training] is better. They know more than the inside trainer. Moreover, they are more professional with salon skills. If we take an outside training, we get the certificate for this course, but if we take training inside the shelter, we get only a certificate from the shelter (laugh).” (Chea, female, 2015)

Cordisco-Tsai, Lim, Nahn. (2018). Experiences in Shelter Care, “Vulnerability in the community due to dramatic difference between shelter and community life”.

“Most of the victims who stayed in the shelter were not successful. They succeeded only 3 to 4 of them. Some of them are working in the organization. Some of them work at different places… They sometimes said that it was easy to live in the organization and they did not do anything. They have someone to take care of them. They have food to eat. They have people to bring the food for them and they can sleep well. They can learn and so on. They thought that it was easy for them and when they go home, they think work at home is difficult for them. They speak badly to the members of the family.” (Nimul, female, 2016)

Cordisco-Tsai, Lim, Nahn. (2018). Experiences in Shelter Care, “Vulnerability in the community due to dramatic difference between shelter and community life”.

The Future of the BLRP

There is much more that could be done to use the data and stories collected over the years in the BLRP to inform and educate young people. Discussion groups, illustrated comic books, case studies and seminars are among the possibilities. One idea taken up by AusCam (a project that works with trafficked women and girls) is to localise the information, presenting the stories in simple, understandable language and well-explained scenarios to make it accessible for prevention programmes with high school children.

Currently, the funding for the BLRP is becoming scarce which makes the future of the project uncertain. All the research staff have commented that they would be interested in continuing their research and, in particular, would like to maintain the relationships they have with the participants. The obstacle is being unable to get time off their new jobs however, if this could be organised, they want to stay in contact with and meet the participants.

In turn, many participants are also willing to continue with the project because they feel it is important to tell their story so that it can help others going through similar experiences. The principal hope among the survivors is that vulnerable young people are warned about the dangerous signs of human trafficking and given advice about how to deal with reintegration into life in their community. This demonstrates the duality of the project that not only is research for policy and programmes on aftercare and social integration possible, but the participants feel that they matter and the researchers themselves enjoy knowing and caring about the people involved.

Judging from the responses of both staff and participants, there is a definite future for the BLRP and other similar projects. There has been an overwhelming positive response to the research approach that has been used, which allowed for participants to trust staff and be able to have someone to talk to during difficult times. There are also many challenges for the future; at present, the global pandemic adds another dimension to research, travel and care of communities. Of course, the usual difficulties must also be considered: stigmatisation from family and community; the existence of the very issues that create human trafficking victims and survivors; and, the ever-present circumstantial challenges of keeping in touch with the survivors. In the future, the project will continue to use its current method of trust and open discussion to build relationships, as this has shown to produce detailed and relevant material to help improve survivors’ lives in their communities.

Publications of the BLRP

Below is a list of thematic papers and annual reports on the BLRP findings and recommendations aimed at practitioners. All are available from the Chab Dai website. Many of these thematic papers are being turned into peer reviewed articles for academic journals, please continue to follow the Chab Dai Coalition’s website and social media for updates on the release of these new publications.

(Eng = English; Kh = Khmer language available):

Miles, G., Lim, V., Nhanh, C. (2020). Children of the Wood Children of the Stone: The Journey of Faith for the Survivors of Trafficking. Thematic Paper (Eng), Executive Summary (Kh).

Tsai, L. C., Lim, V., and Nhanh, C. (2018). Experiences in Shelter Care – Perspectives from Participants in the Chab Dai Longitudinal Research project. Executive Summary (Eng | Kh), Thematic Paper (Eng).

Havey, J., Lim, V., Nhanh, C., Sreang, P., Ou, S., Phallen, P., Kang, C. (2018). Chab Dai Coalition’s Butterfly Longitudinal Research ‘Top 10’ Findings…so far…. Illustrated Report (Eng).

Davis, J., Havey, J., Lim, V., Nhanh, C., and Sreang, P. (2016). The Forgotten Cohort: An Exploration of The Themes & Patterns Among Male Survivors of Sexual Exploitation & Trafficking. Thematic Paper (Eng | Kh).

Brake-Smith, J., Lim, V., and Nhanh, C. (2015). Economic Reintegration of Survivors of Sex Trafficking: Experiences and Expressions of Filial Piety and Financial Anxiety. Thematic Paper (Eng), Working Paper (Eng | Kh).

Morrison, T., Miles, S., Lim, V., Nhanh, C., Sreang, P., and Bun, D. (2015). Survivor Experience and Perspectives of Stigma – Reintegrating into the Community. Working Paper (Eng), Thematic Paper (Eng).

Morrison, T., Miles, S., Heang, S., Lim, V, Sreang, P., and Nhanh, C. (2014). Resilience: Survivors Experience and Expressions. Working Paper (Eng), Thematic Paper (Eng).

Miles, S., Heang S., Lim, V., Nanh, P., and Sreang, P. (2014) Reflection on Methodology. (Eng)

Miles, S., Heang, S., Lim, V., Sreang,P., and So, D. (2013). End of Year Progress Report 2013. (Eng)

Miles, S., Heang, S., Lim, V., Orng, L. H., Smith-Brake, J., and So, D. (2012). End of Year Progress Report 2012. (Eng)

Miles, G., and Miles, S. (2011). End of Year Progress Report 2011. (Eng)

Miles, G., and Miles, S. (2010). End of Year Progress Report 2010. (Eng)

References

Babbie, Earl. (2007). The Practice of Social Science Research (12 ed.). Belmont, California: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. p.459. ccftp.scu.edu.cn/Download/e6e50387-38f2-4309-af84-f4ceeefa5baa.pdf

Brake-Smith, J., Lim, V., and Nhanh, C.. (2015). Economic Reintegration of Survivors of Sex Trafficking: Experiences and Expressions of Filial Piety and Financial Anxiety. Chab Dai Coalition. www.chabdai.org/butterfly

Bryman, Alan. (2008). Social Research Methods (3 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. P748. (PDF) Social Research Methods, 4th Edition by Alan Bryman.pdf | Dey BK – Academia.edu

Cathy, Z., & Charlotte, W. (2003). WHO ethical and safety recommendations for interviewing trafficked women. West Sussex, UK: The Printed Word. Ethical_Safety-GWH.pdf (who.int)

CP Merg. (2012). Ethical Principles, Dilemmas and Risks in Collecting Data on Violence against Children: A review of the available literature. UNICEF Statistics and Monitoring Section, Division of Policy and Strategy, New York, NY. Ethical Principles, Dilemmas and Risks in Collecting Data on Violence against Children. A review of available literature – CP MERG (2012) | Resource Centre (savethechildren.net)

Davis, J., Havey, J., Lim, V., Nhanh, C., and Sreang, P. (2016). The Forgotten Cohort: An Exploration of The Themes & Patterns Among Male Survivors of Sexual Exploitation & Trafficking. Chab Dai Coalition. www.chabdai.org/butterfly

Ennew, J. and Plateau, D. (2004). How to Research the Physical and Emotional Punishment of Children. Save the Children International, Bangkok, Thailand. content (savethechildren.net)

Havey, J. (2018). Chab Dai Coalition’s Butterfly Longitudinal Research ‘Top 10’ Findings…so far…. Chab Dai Coalition. www.chabdai.org/butterfly

Marshall et. al. (2014). Voluntary participation and comprehension of informed consent in a genetic epidemiological study of breast cancer in Nigeria. BMC Medical Ethics 15:38. Voluntary participation and comprehension of informed consent in a genetic epidemiological study of breast cancer in Nigeria | SpringerLink

Menard, S. (2002). Longitudinal research (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Longitudinal Research – Scott Menard – Google Books

Miles, G., Lim, V., Nhanh, C. (2020). Children of the Wood, Children of the Stone: The Journey of Faith for the Survivors of Trafficking. Chab Dai Coalition. www.chabdai.org/butterfly

Miles, S., Heang S., Lim, V., Nanh, P., and Sreang, P. (2014) Reflection on Methodology. Chab Dai Coalition. www.chabdai.org/butterfly

Miles, S., Heang, S., Lim, V., Orng, L. H., Smith-Brake, J., and So, D. (2012). End of Year Progress Report. Chab Dai Coalition. www.chabdai.org/butterfly

Miles, G., Miles, S. (2011). End of Year Progress Report 2011. Chab Dai Coalition. www.chabdai.org/butterfly

Miles, G., Miles, S. (2010). End of Year Progress Report 2010. Chab Dai Coalition. www.chabdai.org/butterfly

Morrison, T., Miles, S., Lim, V., Nhanh, C., Sreang, P., and Bun, D. (2015). Survivor Experience and Perspectives of Stigma – Reintegrating into the Community. Chab Dai Coalition. www.chabdai.org/butterfly

Morrison, T., Miles, S., Heang, S., Lim, V, Sreang, P., and Nhanh, C. (2014). Resilience: Survivors Experience and Expressions. Chab Dai Coalition. www.chabdai.org/butterfly

Reimer, J.K., Langeler, E., Sophea, S. & Montha, S. (2007). The Road Home: Toward a Model of “Reintegration” and Considerations for Alternative Care for Children Trafficked for Sexual Exploitation in Cambodia. Hagar & World Vision, Phnom Penh, Cambodia. (No longer available online)

Taylor, L. R. & Latonero, M. (2018) Updated Guide to Ethics & Human Rights in Anti-Human Trafficking. Bangkok. Issara Institute. 5bf36e_1307f698e5ec46b6b2fc7f4391bff4b6.pdf (filesusr.com)

Tsai, L. C., Lim, V., and Nhanh, C. (2018). Experiences in Shelter Care – Perspectives from Participants in the Chab Dai Longitudinal Research project. Chab Dai Coalition. www.chabdai.org/butterfly

UNIAP (2008) Guide to Ethics and Human Rights in Counter-Trafficking: Ethical Standards for Counter-Trafficking Research and Programming. Bangkok. UN ACT |Guide to Ethics and Human Rights in Counter-Trafficking – UN ACT | (un-act.org)