This article was originally published in British Association of Play Therapists journal ‘Play Therapy Issue 89 Spring 2017, p.14-16. Published here with permission from BAPT and the author

It’s Friday 8am and the ‘educadoras’ are gathering for a workshop on ‘ludoterapia’, or play therapy, that I am about to lead. I have spent the week building relationships with the 9 women who are currently expressing some reticence and anxiety about participating. This is usually their meeting time with the psychologist to debrief on their busy working week. They are aware that the session will be different but have no idea what it will entail and what I will be expecting from them.

I am in southern Brazil, in the city of Curitiba, working at a project called The Associação Beneficente Encontro com Deus (ECD), a charity founded in 2000. The charity houses an average of 40 single mother families per year in two residential care homes. The families are sent via the municipal social services and law courts and come from situations of domestic and territorial violence as well as homelessness or extreme poverty. The ‘educadoras’ or ‘carers’ are responsible for the day to day running of the two care homes, providing a safe and nurturing place for these vulnerable families.

At the very heart of ECD is their prime objective: to strengthen the family attachments and relationships thus enabling children to remain with their mothers and within the family structure. They seek to empower the mother, helping to develop her own support systems and independence so that she can be integrated into society along with her children (Santos, 2015a; 2015b). I have had the privilege to follow (and occasionally be involved with) the developing work of the project for the past 14 years since meeting its Founder and Director, an Englishman called Patrick Reason.

The ‘educadoras’ work day in, day out on the ground with the mothers and their children, in very practical ways. The ‘technical team’, consisting of two psychologists, an Argentinean psychoanalyst, and two social workers, have asked me to lead a two hour workshop introducing play therapy to these hardworking ladies. The aims are simple, to emphasize the importance of play for both the individual child’s development and the strengthening of the attachment between mother and child. I hope also to encourage the ‘educadoras’ to consider new ideas of how they could offer play opportunities for the children and the mothers during the day to day life at the project without always having many toys available. I want the session to be practical and fun, to bring light relief and support rather than any added pressure to them.

Although play therapy exists in Brazil, my research so far has found it to be scarce and based around universities in particular cities. It is little heard of and definitely not a therapy easily accessible to children and their families. I briefly introduce myself, my work and what play therapy is to the group who listen attentively. My next question unexpectedly leads to an eruption of discussion! I ask each one to think back to her own childhood and to recall a favourite memory of playing. What emerges is that most of them have come from poor families where there was little if any money to spend on the luxury of having toys. Instead they used anything available to ‘become’ what they desired or needed it to be. A corn on the cob, still in its green skin with yellow ‘hair’ poking through, became a doll, a baby or a person. A plank of wood became a car, a home, a bridge, a flying machine. A battered tricycle took you on many an imaginary journey anywhere you wanted to be around the world.

How perfect to highlight the imagination and creativity of children! How grounding to reflect that ‘toys’ are not the only vehicles for conjuring up a playful experience! A child’s predisposition to play, to enter the world of fantasy, to project their experiences onto objects, to communicate through their most natural ‘language’ isn’t dependent on the finances available, rather on those around them being open and accepting of their play in whatever form it takes.

We spend the next 30-45 minutes unpacking the Embodiment-Projection-Role developmental paradigm (Jennings, 1993; 1999) together. I explain each stage and together we create a mind map for each, discussing practical ways that they can offer appropriate experiences within the structure of the daily routines and chores. Having spent half of my own life in Brazil, I have found Brazilians to be very aware of and in tune with their own senses. Their culture reflects so much colour, warmth, music, touch, vibrancy, and a richness of food and smells. It isn’t hard for the group to think of many ideas but the practicalities of allowing particularly messy play is a challenge for them. Part of their responsibilities is to keep the two houses where the mothers and children live clean and tidy. To allow messy play knowing that they would then be cleaning up does not sit very comfortably. I hope to offer them an opportunity to experience sensory play within the workshop that might encourage the breaking down of this barrier.

Another very appropriate area of discussion that emerges is around the expression of anger, aggression and aggressive energy. Nearly all the children that come to the project have been victims of or witnesses to violence and domestic abuse in some form. A significant proportion of these express their experiences through anger and aggression themselves. Although most of the ‘educadoras’ were accepting of this need they were searching for ways to allow and support this expression in safe and containing ways. Together we discussed possible solutions that could fit within their specific situations. Keeping McCarthy (2012), Oaklander (1988) and Blom (2006) in mind, I particularly link it back to embodiment play, offering the children opportunities to express themselves through messy play like play dough and paint for example, and projective play, where they could explore themes of violence and anger through creating stories as containers for their experiences. One of the ‘educadoras’ shares a relevant vignette of accompanying a child through his imaginative play over a number of weeks. He would come along side her everyday and narrate stories to her as he played with a few figures and as she carried out her daily tasks. She would listen, reflect back what he was sharing and when possible join in his play with him. Over time she saw the changes within him, transitioning from a vulnerable, easily upset and angered child to a calmer, more confident individual.

Within this, we also consider the role of the superhero. Not surprisingly Hulk is described as a favourite amongst the children along with Spiderman and Captain America. The opportunity and ability to role play a powerful, strong, indestructible character that is able to save others from injustice, violence and fear is I believe key to the children regaining a sense of control and sense of self following their harrowing experiences. I urge the ‘educadoras’ to accept and affirm the heroes and superheroes that the children want to explore and role play as vital to their healing and development. (Cattanach, 1997)

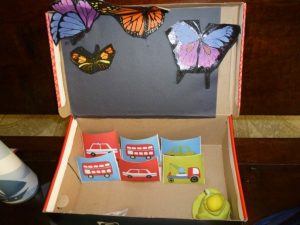

To bring all the ‘theory’ to life, I have brought along some homemade play dough, empty shoeboxes, scissors, glue and a variety of coloured and decorated papers to the workshop. Firstly I encourage the group to spend time enjoying the texture and experience of playing with the play dough themselves. I then ask them to create a character with it. My final instruction is to use the rest of the materials to create an environment for that character. The room fills with laughter, excitement, fun, banter, imagination and creativity. It is very special to be a part of and when it’s time to end, the ladies protest asking for more time. They tease the psychologist who has also participated, saying they expect future meetings to have practical elements to them from then on.

To end I share with you a couple of examples of the work the ‘educadoras’ made. They were aware that they were projecting their own experiences within their work and also were happy to share these openly.

‘Maria’ was involved in a car crash in the week leading up to the workshop. She was very shaken up and experiencing considerable pain in her neck and shoulders. A physiotherapist was helping relieve this pain through massage and exercises. Maria believed very strongly that an angel had been protecting her as the crash could have been much worse and she could have been seriously injured.

Her sister, although not in the car, was very upset and wanted to express her frustration with the chaotic traffic in Brazil and the lack of proper traffic police.

‘Neide’, like a number of the ladies, holds her own family very dear and wanted to express her love, care and appreciation of her home and family. To be able to provide a nurturing and loving home both practically and emotionally, is very important to these ladies.

As I return to England, I hope that I have inspired the group to continue be imaginative and creative both for themselves and in offering play opportunities for the children and mothers that enter the project for refuge. I certainly was challenged and touched by the work they do and the understanding and compassion that they show to those in their care.

Helen Gedge

- I have been granted permission to share this work and the photographs in this article.

References:

Cattanach, A. (1997). Children’s Stories in Play Therapy. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Blom, R. (2006). The Handbook of Gestalt Play Therapy: Practical Guidelines for Child Therapists. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Jennings, S. (1993). Play Therapy with Children: A Practioner’s Guide. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications.

Jennings, S. (1999). Introduction to Developmental Play Therapy: Playing and Health. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

McCarthy, D. (2012). A Manual of Dynamic Play Therapy: Helping Things Fall Apart, The Paradox of Play. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Santos, L.B. (2015a). Acolhimento Conjunto: Um Novo Olhar Para o Educador. Curitiba: Associação Beneficiente Encontro com Deus.

Santos, L.B. (2015b). Projeto Técnico: Serviço de Acolhimento ECD. Curitiba: Associação Beneficiente Encontro com Deus.

Oaklander, V. (1988). Windows to our Children: A Gestalt Therapy Approach to Children and Adolescents. NY: The Gestalt Journal Press.