In this essay, I will look at the results of a survey carried out by my employer last year to assess the effectiveness of the school’s approach to racism within the organization, and the support offered to staff and children from BAME backgrounds within the organization. I would like to acknowledge that it was asked of me to do a research project, and I haven’t done this as a matter of choice. I feel that this work that has begun in trying to tackle subconscious bias is important to the life outcomes of the children in our care. This isn’t something that can be tackled with one piece of work, but will require ongoing research, conversation and action. I believe that this is the area that might more meaningfully impact the children in our care. In the first part, I will introduce the organisation and look at the results of the survey. In Part two, I will explore how we could draw upon our understanding of psychodynamic principles to create a better, more meaningful approach to engaging with subconscious bias. Finally, in Part three I will consider how we can apply what we’ve learned, and what the conversation might look like once we have arrived at a place where we can have these conversations.

Before I begin, I should explain why I became interested in this subject. I grew up in a small town in South Wales, which looking back, was a very insular homogenous environment. I went to a Welsh speaking school that was 100% white-Welsh. I had no interactions with anyone from the LGBT+ community or anyone from a BAME background until I went to University. Whilst at University in Swansea, I continued to surround myself with people of the same socio-economic and ethnic background as myself. I wouldn’t have described myself as racist or homophobic, I considered myself to hold very reasoned, well thought out arguments that, now, frankly, I’m ashamed of. Moving to Oxford a decade ago I began to mix in different circles to the ones I was comfortable in. Slowly, but surely, the preconceptions I held were dismantled, as I couldn’t maintain the arguments when properly challenged in an environment I felt was safe, amongst my new friends. I say this, to say that I don’t feel that people who hold discriminatory opinions are ‘stupid’ or ‘incapable of reasoning’. On the contrary, as the psychologist Jonathan Haidt (2012, p.24) puts it, “They were working quite hard at reasoning. But it was not reasoning in search of truth; it was reasoning in support of their emotional reaction”. When Darren Wilson fatally shot Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri in August of 2014, the Black Lives Matter Movement hit an international audience. I found myself shocked, and captivated. I was too interested in the self-preservation of my own world view to take any notice of the Macphearson Report, when it concluded in 1999 that the Metropolitan Police in London was institutionally racist. By 2015, in Oxford, I was ready to pay attention. I had found myself going on a journey from ignorance, to attempting to understand, and to better understanding, that I feel compelled to write my essay on this subject. Importantly, it was through a containing environment that I was able to begin to see things differently. It is my hope that this will contribute to a better understanding of how we, as an organization, can make a more inclusive environment for all members of staff, and benefit collectively from the wealth of cultural knowledge that is too often overlooked.

Part 1. The Survey. Analysis and implications.

I work at the Mulberry Bush School (MBS). MBS is a residential school accommodating traumatised children aged 7-12. The focus of the school is to provide holistic therapy to the children in their care. My primary role is to support the few children who are there, 52-weeks a year, and to support them during the holidays. As this makes up 14 weeks of the calendar, naturally a large part of my role is to work with the children within the main school, supporting the children in their 38-week houses. This involves supporting them in all aspects of their daily lives. Due to the level of trauma experienced by the children, many of the behaviours displayed can be very challenging and complex, ranging from aggressive, sexualised behaviour to children with complex social needs. Taken from the MBS statement of purpose, “the Mulberry Bush is a therapeutic community providing a highly integrated combination of therapeutic education, care and treatment for primary aged boys and girls with severe social, emotional and mental health difficulties. […] It also works intensively with children’s families” (2018, p.5). The children will extensively use racist language and behave in prejudicial ways, particularly when dysregulated. Historically within the organization, this has been understood as means for the children to engender a strong reaction from adults, and as a means of controlling their environment. This understanding of behaviour as communication may be sufficient to explain the behaviour, but falls far short of addressing the impact of the use of this language on the community.

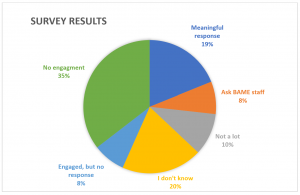

The tragic murder of George Floyd last summer marked a global awakening to the discrimination that Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) people face, on a daily basis, across the Western world to this day. Within MBS, this also coincided with a small number of individuals having the courage to openly challenge the school’s responses to the use of racist language and opened the conversation to wider issues of subconscious bias across the organisation. Within a month of George Floyd’s murder, MBS had sent out a survey to the whole organisation to ask. The two questions were “What already happens at MBS that is helpful to BAME members of staff?” and “What could happen at MBS that would be helpful to BAME members of staff?”. Of the 127 members questioned, 82 people responded. To illustrate this more clearly, I have put the results in the form of a graph.

This is slightly higher than the number of responses the school would usually expect. This would imply a willingness to engage, however let’s briefly consider the different categories of responses. First of those that responded, almost half responded with “I don’t know” (30%) or “Not a lot”(16%). Both of these statements may be true on a local level, however show a lack of willingness to understand what is in fact being done, or what could be done better. The school has several avenues that could, and should be being used to address these issues. There are regular supervisions and regular reflective spaces, for example. These mechanisms have been set up precisely to discuss issues such as these. These things are being done by the school however they are not being used by the staff. By the time the survey went out to all of the staff, there was also a “Privilege and Prejudice” group set up by the school. Information about this went out to all members of staff. All staff will have known about this, but many of the respondents seemed unaware of this when filling in the survey. For whatever reason, when asked, many of the staff that did respond couldn’t bring these responses to mind.

Then we have “Ask the BAME members of staff” (12%). To many people, it may appear a thoughtful, supportive response to say “ask the BAME members of staff.” I myself responded this way, before I began my research for this essay. This may be a sincere attempt by White Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASPS) to seek to create more meaningful outcomes. This acronym is attributed to Andrew Hacker in an article written in 1957, and is used extensively throughout North America and Australia, but is relatively unknown in the UK. However, viewed from another perspective, could be considered a subconscious (or even conscious) attempt to absolve themselves of responsibility.

There were also a significant number of people (12%) who responded to the survey, however didn’t write any answer to the questions. Whilst analysing the results of the survey, I found myself trying to pick apart why those who replied (myself included) couldn’t offer a more robust response to two simple questions. Given the enormous impact of the Black Lives Matter Protests happening around the globe at the time, I wondered why the survey drew such a high volume of poor responses. I began by thinking about how I could have written a different set of questions, questions that might illicit a more thoughtful response. I began to think about the people I work with, and their general willingness to help. In trying to think of “better questions” I realized that the barriers to engaging staff meaningfully with this issue may not lie in the effectiveness of the questions. It should be held in mind that these are the responses from the staff who actually engaged with the survey. 35% of the organisation did not engage at all. There will be a myriad of reasons for this lack of engagement. Many will have been busy, generally stressed, impact of covid, many meant to get around to it… But my suggestion is that people are not engaging in these conversations around race and the impact of subconscious bias not because they’re racist and/or don’t care, but because they’ve subconsciously pushed it out of their minds. I began to wonder what the subconscious barriers were to engaging with this type of discussion.

It shouldn’t be taken for granted that these issues are important to engage with. There is a significant number of people in the UK who do not see these issues as relevant to them. Recently, the English Football Association (2021) had to appeal to English football fans not to boo the national team as they took a knee to show their support of equality within the game. These issues that we have in society will need to be addressed on a National level, but I will concentrate my thinking around how we may be able to engage the staff at MBS primarily. Are there members of staff that think that these issues aren’t worth talking about? If so, they didn’t responded to the survey. In order for us to think about how to be a truly inclusive organisation, we must be able to engage with these conversations. Given the prevalence of objection to anti-racist conversation across the nation, it would be unusual if not a single member of staff held similar views to those England fans. There needs to be engagement in order for us to learn and grow as an organisation. From Ancient times, it has been said that there are three ways to bring someone over to your way of thinking. The great orator from Ancient Rome, Cicero “often said…”, translated by James M. May (2016, p. 16) “we bring people over to our point of view in three ways, either by instructing them [that is, logos] or by winning their goodwill [that is, ethos] or by stirring their emotions [that is, pathos]”. Maybe today with a deeper understanding of psychodynamic principles, we can try a fourth way. By looking at what subconsciously stops us from engaging in these conversations, we will allow the conversations to flourish. I suggest that with an open dialogue, then we will be able to begin to answer the question posed in the survey “What could happen at MBS that would be helpful to BAME members of staff?”.

Part 2. The Psychodynamics – Understanding the barriers to the conversation

It appears that the reluctance for white people to engage in conversations around race is not limited to the MBS. There have been numerous articles in recent years discussing this, such as Natalie Morris’ (2021) article in Metro News, “The damaging impact of white people being too afraid to talk about race”, or the BBC’s Megha Moahn (2021) “talking to my white friend about race – for the first time.” I wondered if there was a way we could use the psychodynamic approach, embedded withing the MBS to create an environment more conducive to this conversation. I feel there are many parallels with the barriers to engagement with this discussion to psychoanalytical theory. There would be many different avenues to explore. Given more time, I would like to consider some other theories, such as Attachment Theory or Tajfel’s Social Identity Theory, however I would like to focus on the theories I feel most relevant to bringing about more immediate change. I will briefly discuss the role of ‘splitting’ as a barrier to conversations around race, and then move of to my main argument, and potential solution, of ‘containment’.

There may be some parallels to be drawn here from psychodynamic theory developed by Klein in the 1950 discussing infant development. Adrian Ward (1998, p.57) explains “…in the theory of infant development (Klein 1959), splitting refers to the way in which the child may protect him or herself against acknowledging powerful feelings such as distress or anxiety by unconsciously allocating all “bad” qualities to one person or relationship and all “good” qualities to another (or to the self), rather than being able to manage a mature and balanced relationship in which ambivalence or anxiety is contained”. But how could this apply to white people, and their unwillingness to discuss issues around race? For some white people, the idea that they could be considered even passively complicit in anything that could be called racist is simply abhorrent. For many, simply the word ‘racist’ conjures the horrors of America during the Jim Crow years, the Ku Klux Klan, and the lynching of Emmet Till. This is, understandably, could come close to a definition of ‘Pure Evil’. Dolly Chugh (2018, p. 7) explains “While none of us are good all the time, and some of us are far from good a lot of the time, we still see ourselves as good.” Chugh continues “I want to be seen as a good person… Evidence to the contrary is a self threat”. And if many people hold an idea about racism as described above, they will not engage in conversations around racism, for fear of being considered someone who holds the views of the horrors listed above. So we have a situation where on the one hand, we have ourselves (all good) and on the other we have racism (all bad). Returning to the quote above, but replacing ‘child’ with White Anglo-Saxon Protestant, and adapting it accordingly, “the [WASP] may protect him or herself against acknowledging powerful feelings such as distress or anxiety by unconsciously allocating all “bad” qualities to [racism] or [racists] and all “good” qualities to another (or to the self), rather than being able to manage a mature and balanced relationship in which ambivalence or anxiety is contained”. I feel that the link between this psychodynamic mechanism and engagnemt in discussions around race is self-evident, once viewed from this perspective. In order to fully understand the statement above, as amended for use in our community, we will need to understand what Klein means by the term used at the end of the quote; ‘containment’.

We work with children who have suffered serious trauma at an early age. This will have had a significant impact to the “world view” the child develops. Adrian Ward (1998, p.13) explains “The psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott would say that the capacity to sustain the sense of the inner world develops during the first year or so of life, out of the child’s experience of being ‘held’ emotionally as well as physically by the parent(s). He calls this whole experience the ‘holding environment’. As the child’s most primitive and unthinkable anxieties are contained and understood by the parent and the child learns to trust the parent, so that child gradually learns to recognise thoughts and feelings, and develops the ability to think as well as the capacity to symbolise and to play”. As we work with the children, we would like to create a safe environment for them to explore their ‘primitive and unthinkable’ thoughts, and for us as workers to help the children to process these thoughts. Another psychoanalyst, Bowlby (1988) draws on Winnicott’s work and “…argues that in providing a secure base from which to explore and express thoughts and feelings…provides the child with a secure base from which to explore the world. A basic task of emotional holding is the provision of a secure base from which the child can make actual and metaphorical sorties into the outside world and to which s/he can return, knowing that there will be a welcome, physical and emotional nourishment, comfort if distressed, and reassurance if frightened.” Paul Greenhalgh (1997, p. 108).

It occurred to me that this same mechanism could be at play when it comes to white people discussing issues around race. As there has become an increased understanding and awareness of implicit bias, and subconscious racism, this identity developed over decades, has been challenged. There are people in society that would like to think that racism is a thing of the past, and that they couldn’t be complicit in subconscious racism. There is a lack of understanding about what systemic racism means, and people hold on to the idea, as Robin DiAngelo (2018, p.73) puts it, “The simplistic idea that racism is limited to individual intentional acts committed by unkind people is at the root of virtually all white defensiveness on this topic”. I would like to acknowledge that I am obliged to make sweeping generalisations, and that when I refer to “white people”, of course, I’m not talking about “all white people”. When I speak of “white people”, I’m speaking of the world view developed by a culture built on colonialism – For brevity, I’ll continue to use the acronym ‘WASP’.

Considering the similarities between the child’s ‘inner world’ discussed by Bowlby and Winnicott above with the collective identity, or ‘inner world’ of a white person in the UK, some similarities may be drawn. The child suffering from trauma has developed a sense of identity or inner world rooted in one setting, only to have to develop a new sense of self when the environment of early childhood has changed. Similarly, the collective environment that the majority of white people grew up in with relation to race, is also changing, and the white person needs to redefine their sense of identity in order to fit in to a just society. To engage this person in conversation, the environment needs to be a ‘containing environment’. To return to Paul Greenhalgh’s earlier quote, I’ve added a minor modification “As the [WASP]’s most primitive and unthinkable anxieties are contained and understood by the [community at MBS] and the [WASP] learns to trust the [community at MBS], so that the [WASP] gradually learns to recognise thoughts and feelings, and develops the ability to think”. If we can create a suitable holding environment for the white people in the organization, we may find that these overwhelming ideas around identity and guilt from the past may be tolerated, survived, and managed. To return to Paul Greenhalgh, this time with no need for additions, we need to create an environment “of holding or containing difficult feelings, to show the feelings can be tolerated, managed, thought about and understood as having meaning, so that one might develop a different relationship with them”.

The creation of this holding environment should be the responsibility of the entire community. There may appear to be some kind of paradox here. How could the white members of staff feel to be ‘held’ or ‘contained’ if they fear an unsurvivable disaster if they were to dare to talk about race, if not by being ‘held’ by BAME members of staff? Thankfully we can move away from the sweeping generalization made about all white people now, and consider the different perspectives that white people within our community have. I feel strongly that the onus for the work in creating a ‘holding environment’ for white members of staff to feel like their feelings will be tolerated, and processed DOES NOT lie with the BAME members of staff. The purpose for starting this research was to try and find a way that the whole community would be more supportive of BAME staff, not to further burden a small minority of staff with the work of holding this environment. From conversations that have begun to be had across the school, there are a minority of white staff that are comfortable to be able to have these conversations around subconscious and systemic racism. It should be acknowledged that these conversations began with a minority of BAME staff who had grown tired (an understatement) of watching the organization deal with overt racism from the children, and subconscious racism from staff, inadequately. It would have been far better to have arrived where we are now without BAME staff having to do most of the work, but now that we have begun the conversation, it would be grossly unfair to expect them to continue this work.

One difficulty in asking white members of staff to continue to work to maintain this holding environment for others is the imperative simply doesn’t exist. Well meaning white people can chose whether to engage in these conversations. Put simply, when a white person tires of conversations around racial identity, they can absolve themselves of the burden. Judy Ryde (2009, p.38) says “The idea that whiteness is the normal form which others deviate is such an insidious and subtle idea that it may well be the biggest single factor that keeps white privilege in place… Whites alone can opt out of their own racial identity, they proclaim themselves non racial”. To put it bluntly, to decide to not see things from the perspective of race is not an option available to BAME staff.

I believe we are at a turning point in the organization at the moment. We have a small number of white people willing to carry some of the burden of having these discussions and maintaining a ‘holding environment’ in the organization, the question remains will they maintain this burden, and continue to hold this responsibility next month, year, in the years to come? If we can arrive at a point in the near future where the white members of staff can create, and maintain an environment that’s sufficiently containing for other white staff to explore and process their new understanding of race and identity, it should be remembered collectively by the organization where this work began. As I mentioned above, this work began with BAME members of staff talking on a burden out of exasperation, to create an environment sufficiently containing for the minority of white staff to engage with these conversations. I’m hoping that this burden could be shared moving forward, without forgetting where this work began.

Part 3. What next? How to apply what we’ve seen to a work place setting.

Once we have created an understanding that it’s through creating a containing environment to have these discussions, and an understanding that it’s the responsibility of the whole community to create this, what shall we do? There are some talking points that come up time and time again when I hear people reluctantly share their dissent around issues of race. I’ll run through a few of the examples people use to justify and maintain a worldview that works to keep BAME people at a disadvantage. This is by no means to offer direct rebuttals when these situations arise in the workplace, but intended to get the reader to think about how they themselves respond to these ideas, and how they might respond in future, keeping in mind that it’s through fostering a containing environment that the children in our care, as well as our staff, are able to grow.

It is said by some that ‘race is a social construct’, that ‘race doesn’t exist’. This may be true on a biological level, but fails to take into account that we have set up our institutions in this country on the basis of this ‘social construct’. Ali Rattansi (2007) argues in the first part of his book “Racism: A very short introduction” that looking for differences between different races from a biological perspective has no scientific support. He makes this argument to stress that the differences we may attribute to people has no basis in biology. This has been misinterpreted by some to say that ‘race doesn’t exist’ and so racism can’t exist. Adam Rutherford (2020, p.26) points out “Race most certainly does exist because it’s a social construct.” We have a situation that has been well understood for many years. To be clear, there are racist people in the world, however in trying to address the issue of subconscious or implicit racism, we need to understand the mechanisms at play. Malcolm X (1966, p.489) talking to a white American Ambassador to an African country, said in 1964 “What you’re telling me is that it’s me is that it isn’t the American white man who’s racist, but it’s the American political, economic, and social atmosphere that automatically nourishes a racist psychology in the white man”. These ‘social constructs have a very real bearing on society, if not on biology.

I have heard it said in the work place, as well as with conversations with my family/friends a sentiment along the lines of “I just treat everyone the same”. Implied in this statement is that they don’t have any ‘blind spots’ when it comes to considerations around prejudices. Chugh (2018, p. 34) says “In fact, if you find yourself thinking or saying “I don’t think I have any blind spots” then that is your blind spot”. What the statement above says more directly, is that if we were to treat everybody ‘the same’ then we would live in an equitable society. This fails to consider the barriers that are placed in the way of some groups. The same author, in her book (Chugh, 2018) “The person YOU mean to be – How good people fight bias” used the metaphor of headwinds and tailwinds to help illustrate the point. It’s not that people from certain backgrounds cannot succeed in this society, but that some people face ‘headwinds’ on their way. Inversely, not everyone who is white is guaranteed to succeed, but they will have a ‘tailwind’ gently helping them along. To fail to see these invisible winds that some people either have behind them, or facing them, is to find yourself with an inaccurate representation of society. Chugh (2018, p.65) “Our failure to see systemic headwinds and tailwinds in the world around us leads us to blame the people facing the headwinds. As a result, we confuse equality and equity. Equality says that we treat everyone the same, regardless of headwinds or tailwinds. Equity says we give people what they need to have the same access and opportunities as others, taking into account the headwinds they face, which may mean differential treatment for some groups.”

There will also, inevitably, come the rebuttal ‘but what about reverse racism?’ While it’s true that all people in the world will hold prejudices, and some people will act on those prejudices, the impact of these prejudices are not backed up by the mainstream societal institutions. I may be treated slightly unfavorably in some circumstances for being Welsh. There are some ways that being Welsh in England help me to glimpse to a very narrow degree some of the issues facing BAME people. On a daily basis I’m asked to repeat my name several times, and regularly encounter people who deliberately mispronounce my name because ‘it’s too difficult’. However as I am a white, straight, male, the impact on me stops there. It’s tiring, but very limited, as I have the benefits of the ‘tailwinds’ in every other part of my life. Maybe 200 years ago, prejudice against Welsh people could be considered racism, but today, prejudice against the Welsh amounts to just that, prejudice, without the weight of the institutional racism to back it up. It would be unreasonable to equate my negative experiences of being Welsh in England to racism, as Robin DiAngelo (2018, p.22) explains that “People of colour may also hold prejudices and discriminate against white people, but they lack the social and institutional power that transforms their prejudice and discrimination into racism; the impact of their prejudice on whites is temporary and contextual”.

These are uncomfortable conversations for white people to have, for the most part. As I have said, acknowledging the ‘headwinds’ faced by some, could make others feel guilty. To try to reconcile English patriotism with the reality of the past, whilst still maintaining your sense of identity does require some reconciliation. Returning to DiAngelo (2018, p. v) “Though white fragility is triggered by discomfort and anxiety, it is born of superiority and entitlement… it is a powerful means of white racial control and the protection of white advantage”. To be able to self-declare this subject ‘too difficult’ is a privilege only available to some in society. And further suppresses the conversation. If anyone were to say ‘I don’t like thinking about this’ and their interlocutor were to persist, then it would be they that were perceived as antagonistic. My hope is that the staff at the MBS would understand why these statements are not conducive to bringing about a more just community.

Conclusion.

I had some level of anxiety when I set about discussing this subject as a focal point for this essay. I have no doubt, that some of the ideas I have discussed will provoke a strong reaction from some readers. I also would like to acknowledge that I am continuing a process of learning. If there are ideas that will be challenged, I would welcome that challenge. Not with a view to be able to prove myself right, but with the knowledge that there will be growth resulting from the conversations that will follow, ultimately, to provide the children in our care with a more rounded environment from which to grow. I don’t expect that the publication of this essay will bring about much change, but I do hope to contribute to a growing discussion across the organization, and hopefully a growing discussion nationally. I was determined that the survey that went out would not be left on a metaphorical shelf. The ethical implications of bringing this broader understanding of ‘headwinds’ and ‘tailwinds’ could not be clearer. I hope that in the following months and years, that maybe some of the ideas I have discussed, particularly the understanding that it’s through fostering a containing environment for all, will be taken forward and held in mind by the organization leaders. I myself have been very open with my colleagues and encouraged a more open and honest conversation. From my experience, the progress will be painfully slow for those ready to have these conversations, and will happen too quickly for those who aren’t. There’s no ‘silver bullet’ to address subconscious racism. Moving forward, this will need to be an ongoing piece of work for each individual, team, department, organization to begin, and to bring people along with them. As an organization, we have previously attempted to tackle the children’s’ use of racist language from a child centered approach. It’s my hope that building on the arguments I have made above and buy adapting our approach to one centered on the understanding by the staff of the issues we face when trying to confront subconscious bias, that the benefits will be felt by the children, by the staff, and by the wider society. I have no idealistic expectation that things will change overnight, but I’m sure that the only way anything will change is by active engagement. To quote the great civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. speaking in 1967, “There comes a time when silence is betrayal.”

References.

BBC Sport (2021) Available from: Uefa Euro 2020: Respect England players’ wishes over taking a knee, says FA – BBC Sport [Accessed: 30/6/2021].

Chugh, D (2018) The person YOU mean to be. London: HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

Cicero, M, A. Translated by James M. May (2016) How to win an argument. Oxford: Princeton University Press.

DiAngelo, R. (2018) White Fragility. London: Allen Lane.

Greenhalgh, P. (1994) Emotional Growth and Learning. London: Routledge.

Haidt, J. (2012) The Righteous Mind. London: Penguin Books.

King, M L Jr. (1967) Speech Delivered at Riverside Church, New York City. Available from: American Rhetoric: Martin Luther King, Jr: A Time to Break Silence (Declaration Against the Vietnam War) [Accessed: 30/6/2021]

Macphearson (1999) The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry. London: The Stationary Office.

MBS Curriculum policy (February 2019) Aims, part 3.

Mcmahon, L, Ward, A. (1998) Intuition is not enough. London: Routledge.

Morris, N (2021) Metro News. Available from: The damaging impact of white people being afraid to talk about race | Metro News [Accessed: 30/6/2021].

Mohan, M (2021) BBC News. Available from: ‘Talking to my white friend about race – for the first time’ – BBC News [Accessed: 30/6/2021].

Ratansi, A. (2007) Racism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Ocford University Press.

Rutherford, A. (2020) How to Argue with a Racist. London: Weidenfield & Nicolson.

Ryde, J (2009) Being White in the Helping Proffession. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Shapiro, F (2012) Letter to the New York Times. Available from: The First WASP? – The New York Times (nytimes.com) [Accessed: 30/6/2021].

The Children’s Act (1989), Section 22, Part 3.

X, M. Haley, A. (1966) The autobiography of Malcolm X. Great Britain: Hutchinson.