Exploring the Archives for materials related to this issue’s theme of youth offending, I immediately turned to the National Childcare Library, part of the PET Archives and Special Collections.

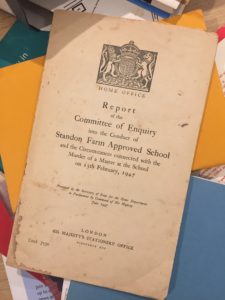

The Library is a fantastic resource for anyone interested in the history of childcare, including those researching society’s response to youth offending over the last century. But as I rummaged through the stacks, there was one pamphlet in particular that stood out for me.

Standon Farm was opened in 1885 by the Church of England Waifs and Strays Society. It operated as a Certified Industrial School until 1926, and then as an Approved School from 1938. By the 1940s, Standon Farm was providing residential care and education for eighty boys aged ten to sixteen who were assigned to the School by the courts.

Standon Farm was opened in 1885 by the Church of England Waifs and Strays Society. It operated as a Certified Industrial School until 1926, and then as an Approved School from 1938. By the 1940s, Standon Farm was providing residential care and education for eighty boys aged ten to sixteen who were assigned to the School by the courts.

However, it was events on the afternoon of 15 February 1947 that would make Standon Farm infamous.

That afternoon, nine boys actioned a plot to murder the head master, Thomas Dawson. Having previously liberated ammunition from Dawson’s own quarters, the boys had successfully stolen rifles from the School’s Cadet armoury when they rounded a corner to be confronted by assistant master, Peter Fieldhouse. In the panic of the moment, one of the boys shot and mortally wounded Fieldhouse. The boys scattered, fleeing cross country on foot in heavy snow. The bad conditions meant none of the group made it very far and by nightfall all the boys were in custody at the local police station.

The events of that afternoon were so shocking, and the failures so many, the incident sparked a public enquiry.

The resulting report into the murder and aggravating factors at Standon Farm came at an interesting moment in the history of youth offending. It marked fifteen years since the passing of the landmark Children and Young Persons Act 1933 which had established the Approved School system leading to Standon Farm’s own reclassification and change in management.

It also came less than a year prior to the Criminal Justice Act 1948 which prevented children under seventeen from being committed to adult prisons, thereby placing more emphasis on the role of dedicated youth detention centres.

The public enquiry into Standon Farm almost reads as a guide for how not run a community for vulnerable young people. The Headmaster, Thomas Dawson was an authoritarian figure, who had implemented a strict and unjust regime at the School. He enforced collective punishments for minor crimes and misdemeanours; resisted granting licenses to older boys; and placed arbitrary restrictions on how pocket money was spent. Furthermore, the rules were often unclear, especially around licensing, breeding confusion among the child community. Fed by gossip and misinformation, this confusion in turn led to a growing sense of resentment and anger among the boys.

Whilst the atmosphere within the school turned sour, the School simultaneously became increasingly isolated. For example, Standon Farm rarely hosted other local schools for sports matches because of the poor condition of their sports ground. Few teams visited the site, and away games were rarely organised to compensate. An opportunity to mix with other boys was provided at the regular Cadet Camps, however the report notes that Dawson was known to keep tight control over the boys even there, denying them the freedoms other cadets enjoyed. Those compiling the report believed this tight control over the pupils adversely affected both their confidence and self discipline. The isolation felt by the School community was further compounded by the harsh winter of 1946-7 which effectively cut the School off from neighbouring settlements.

Whilst the atmosphere within the school turned sour, the School simultaneously became increasingly isolated. For example, Standon Farm rarely hosted other local schools for sports matches because of the poor condition of their sports ground. Few teams visited the site, and away games were rarely organised to compensate. An opportunity to mix with other boys was provided at the regular Cadet Camps, however the report notes that Dawson was known to keep tight control over the boys even there, denying them the freedoms other cadets enjoyed. Those compiling the report believed this tight control over the pupils adversely affected both their confidence and self discipline. The isolation felt by the School community was further compounded by the harsh winter of 1946-7 which effectively cut the School off from neighbouring settlements.

In addition to the difficulties with establishing local contacts, the school lacked both external governance or a strong internal culture. Standon Farm was without a board of local managers from 1936 until just five months before the murder. During that time the role was partially filled by Church of England Children’s Society managers based 145 miles away in London. Internally, the School had no deputy headteacher, leaving Dawson solely in control of all aspects of the School. A previous inspection of the schoolroom had criticised how badly Standon Farm handled the settling in process for newcomers. The schoolmaster was relatively inexperienced and there was little coordination between departments who were often dealing with similar behaviour issues. In fact, the report goes as far as to suggest that whilst the inexperienced schoolmaster thought the older boys showed no interest in the classroom, most were “frankly bored”.

Perhaps the most damning finding of the report was that there had previously been two cases of firearms breaches at the School under Dawson’s management. In 1943 a boy went missing with a rifle and ammunition taken directly from the Headmaster’s office. The child was later found in a barn loft with the rifle and a note suggesting he planned to commit suicide. Then just a year prior to the shooting of Fieldhouse, two boys absconded with service rifles from the Cadet armoury and attempted to rob a local post office.

Despite these breaches, no attempt was made to limit the availability of firearms on site. In fact it was found that Dawson himself had brought live ammunition onto the School site just a few months before February 1947. Both incidents were attended by the police, yet the constable in charge failed to take appropriate action to investigate how the rifles were acquired so easily by the boys, or to report a breach of firearms.

Whilst the report concluded by recommending reforms to the culture, organisation and governance of Approved Schools, it recommended that Standon Farm itself be permanently closed and Thomas Dawson dismissed.

The Approved School system continued to take in youth offenders across the UK for another two decades before it was finally abolished under the Children and Young Persons Act 1969.

Nicky Hilton, Senior Archivist.

The Planned Environment Therapy Archives and Special Collections at the Mulberry Bush are a free, unique public resource. We preserve and make accessible the histories of therapeutic living and learning in the UK and around the world.