On the 15th March 2019, at a ‘Best Practice Forum’ in the House of Lords, I presented our work, ‘The Emotional Warmth Model of Professional Childcare’ drawing on two evidenced-based research papers by my colleagues Dr Seán Cameron (2017) and Cameron and Dr Ravi Das (2019). This article takes the main points of the presentations to show that science can have a friendly face.

Historical context

We can learn much from children, one twelve-year-old boy was so concerned about ‘fatherless’ children in London, that he funded the first London children’s home with an annual endowment equivalent to about £3.5million. Well, it was actually £600, but the year was 1550 and the concerned boy was no less a person than King Edward VI.

The boy king was an orphan, his mother Jane Seymour died on the 24th of October 1537 a few days after his birth, following postnatal complications. Edward became King at nine years old after his father King Henry VIII died on the 28th January 1547.

Peter Higginbotham (2017) in his book on the history of British children’s homes, explains that King Henry VIII ‘acquired’ Greyfriars monastery during the reformation. Henry gave Greyfriars to the City of London in December 1546, but it remained unused until the boy King made his generous endowment in 1550.

By late 1552 about 340 ‘poor, fatherless children’ were admitted to what became known as Christ’s Hospital. Higginbotham (2017) describes their uniform as comprising a black cap, a long blue coat worn with yellow stockings. Blue because the blue dye was inexpensive and yellow because, in those days, people believed that the yellow discouraged lice, a theory which we will return to.

Sadly, the boy king died from tuberculosis at age 16, perhaps the example of his charity was continued in the ‘Poor Law’ (1601) which was the first act of parliament to provide for children in need. Paradoxically, this legislation is likely to be the origin of negative attitudes to children in public care as they used the words ‘needy and deserving’ which calls for judgment to identify ‘undeserving’ children.

Jumping 387 years on to the year 1988, my colleague Christina Rogers and I opened Ingleside children’s home in London. We contacted the authorities to register our children’s home only to find that no registration was required and there were no guidelines on how to run the home. They did advise that we check planning permission and fire regulations. Yet, had we opened a dog kennel in 1988, we would have been subjected to inspection under the Pet Animals Act 1951 which required standards relating to the animal’s accommodation in respects to size, temperature, lighting, ventilation and cleanliness along with many other requirements.

The first act of parliament which regulated children’s homes was The Children Act 1989 and even with this legislation, it had no impact on our children’s home until its enactment in 1991.

Looked After Children in England

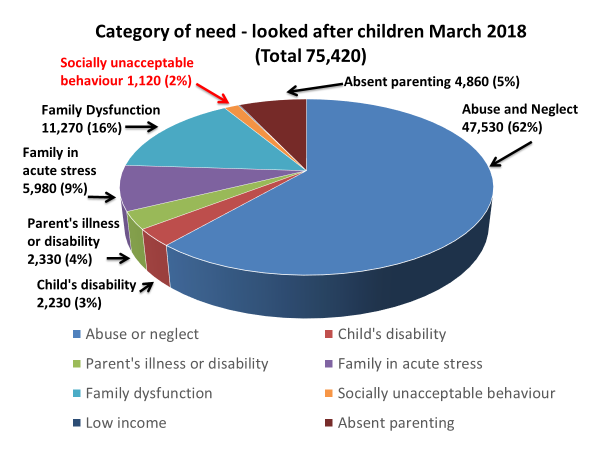

It may come as a surprise to some people to discover that only about 2% of children admitted to care are there because of their socially unacceptable behaviour. Just over 90% of children in care are there because of adult problems including neglect and abuse of children, but the general perspective of many people is that the children are the ‘problem’

Figure 3 is taken from Government statistics covering from the 31st March 2017 until 31st March 2018 ( https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/children-looked-after-in-england-including-adoption-2017-to-2018 accessed on the 5th May 2019)

Budgetary constraints are the paramount consideration

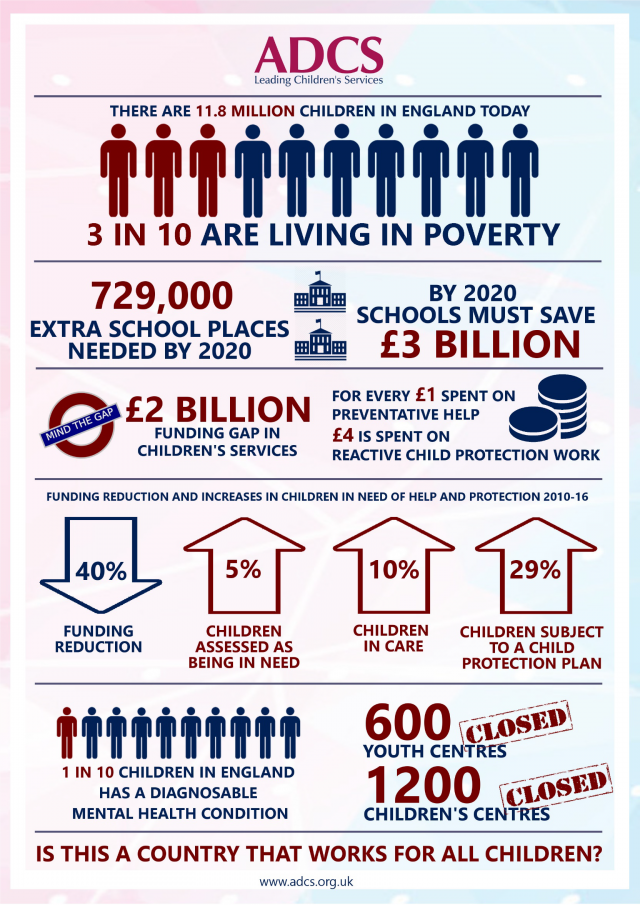

While those in direct contact with children in public care still believe in the principle from the Children Act 1989, that ‘the welfare of the child is the paramount consideration’ we are experiencing a new reality in England, central government have reduced funding to local authorities by on average 40% (see Fig 4 below) forcing the unconscionable position that budgetary constraints are the paramount consideration. In an enquiry by the ‘All Party Parliamentary Group for Children’, chaired by ex-minister for children, Tim Loughton (2018), he states on page 3, ‘Knowing the potentially devastating risks of leaving children without appropriate support, it is unconscionable that we are putting children’s safety at risk by allowing families to fall into crisis before stepping in to help.’ In the same forward Loughton goes on to say: ‘… money is influencing decisions about whether to offer support to our most vulnerable children’.

This harsh reality is clearly illustrated in Figure 4, by the professionals with the responsibility to respond to increasing demands and fulfil legal requirements with decreasing funding. The Association of Directors of Children’s Services (ADCS) report in October 2017 ‘A Country That Works for All Children’ clearly answers the question at the bottom of Figure 4, ‘This is not a country that works for all children’ (My words). The report also offers a way forward: ‘Preventive work to manage demand is the only way to secure a sustainable fiscal future of local government but more importantly, this investment is the best chance we have to turn around the lives of the most disadvantaged children, by closing the gap in terms of attainment, health access to services. Our preventative duties have never been sufficiently funded to enable us to work with families earlier, addressing needs as and when they arise. We are not, nor should we be, a blue light service.’ Page 8. https://adcs.org.uk/assets/documentation/ADCS_A_country_that_works_for_all_children_FINAL.pdf accessed on the 6th May 2019.)

Surprising support for the position in the ADCS report comes from The National Audit Office (2019) an organisation better known for pointing out overspending by Government bodies. In ‘Pressures on Children’s Social Care’ January (2019), The National Audit office points to failings by the Department of Education causing harm: ‘Unless adequate and effective children’s social care is in place, children in need of help or protection will be exposed to neglect, abuse or harm.’ (https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Pressures-on-Childrens-Social-Care.pdf page 6. Accessed 8th May 2019)

Even if we ignore the immorality of leaving children and families who need help and the psychological damage to these children, the All-Party Group for children’s enquiries and the Association of Directors of Children’s services report make convincing financial arguments to address the issues. To add to the argument that investing in preventive work and providing quality support is actually more cost-effective, The National Audit Office (2014) reported on the long term costs to the ‘individual and the taxpayer’ of the 34% of young people leaving care who are Not in Education, Employment or Training (N.E.E.T. page 24) to be £56,000 per year. (https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Children-in-care1.pdf).

A study by Celia Hannon (2010) which looked at quality care and costs, measuring quality with the stability provided to children in care from forming attachments with the adults in the parenting role and having uninterrupted schooling. Hannon compared a stable placement with a nominal Child A, to an unstable placement with a nominal Child B and found that the stable placement cost £32,770.37 less, per child, per year than the unstable placement. Even if we stabilised only half of the current unstable placements, we could save the public purse over £400 million per year. That calculation is based on the 2010 figure without taking account of inflation (https://www.demos.co.uk/files/In_Loco_Parentis_-_web.pdf accessed 8th May 2019). Based on this evidence a new concept can be added to the following quotation attributed to Fredrick Douglass that, ‘It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken adults’ can now be amended to: ‘It is easier AND CHEAPER to build strong children than to repair broken adults.’

Yellow socks, where’s the evidence?

A sceptical reader could check my references and links to test if my arguments are backed up by the evidence which I have quoted. Applying my evidence criterion to children in public care may pose more of a problem. While incidents, assaults, absconding, school attendance, school performance and other data may be available, it is less likely that quantitative and subtle qualitative data on children’s progress are systemically recorded and available. Even when there is information from daily logs, for example, it tends to be random and unlikely to follow any structure or system. Lacking such an objective frame of reference, confused carers will only record what they think is relevant and important, or what fits into their own views of childcare and support. They could even claim that yellow socks repel lice, a widely-held and fanciful theory in children’s homes in Tudor England, which was not based on reality, indeed light colours, such as yellow, attract insects. How many other Yellow Sock ideas exist in our work? You could test this, the next time you or a colleague offers an inexplicable explanation regarding a child in your care, you could apply the ‘Yellow Sock Test’ and ask ‘where’s the evidence?’

An idea which is common today is that children are resilient, but the following quotation by Dr Bruce Perry explains the opposite: ‘Adults interpret the actions, words, and expressions of children through the distorted filter of their own beliefs. In the lives of most infants and children, these common adult misinterpretations are relatively benign. In many cases, however, these misinterpretations can be destructive. The most dramatic example occurs when the impact of traumatic events on infants and young children is minimized. It is an ultimate irony that at the time when the human is most vulnerable to the effects of trauma – during infancy and childhood – adults generally presume the most resilience.’ Perry (1995)

Research-based model of professional childcare

The Emotional Warmth Model of Professional Childcare (Cameron, 2017 and Cameron and Das, 2019) is an applied psychology, research-based model of professional childcare which starts with ‘warmth’ and kindness. This is backed up by empowering each young person by systematically seeking out their often hidden strengths using now well-tested methods from Positive Psychology, an example of this is the work of Alex Wood (2011) who shows that strengths improve longer-term wellbeing. Strengths-based empowerment is also a driver behind training and consultation with the adults in the parenting role, as we see their positive relationships with the young person in their care as the basis for therapeutic change. Children’s home staff and foster and adoptive parents have described this childcare model as ‘the friendly face of science’.

For transparency and to ensure that everyone understands and agrees what needs to be done, a structure which contains a shared language, clear goals, agreed on priorities, and ongoing records of progress, are all required. This enables accountability and following a scientific, research-based approach enables the evaluation of services to children in public care and offers the following:

- The adults in the parenting role and those managing them have a systematic, theoretical, research-based approach which points to what they need to do and why they need to do it.

- Those paying for the service can check what’s working for each individual and that they are getting value for money.

- Ofsted, local inspectors and managers can check for quality and that legal requirements and standards are being maintained. When relevant data are ‘baselined’ and collected at intervals, inspections can monitor what has been achieved for each child against the baseline.

- Family members and those with an interest in the child can seek explanations regarding the theory behind the specific tasks and the rationale for work with their particular child.

- The child is central to the process and the transparency of the approach ensures that they can share their opinions and views, read and ask questions so that they too know and understand what and why a particular task or approach is taken (with sensitivity to their level of understanding).

- The child, as an adult, can access the historical records of their care to reassure themselves that those responsible for their care discharged their duty using the best knowledge available at the time.

Measuring change against a baseline

As early as possible in our work, we train the adults to make objective observations, count what they see and make a baseline for each young person. The baseline is an online assessment procedure or ‘progress and development checklist’. This is structured around the eight Pillars of Parenting (listed below) in order to identify specific priority parenting needs for each child. This is followed by the trauma phases of the Cairns model (also listed below) as a measure of trauma and emotional adaptation. Subsequent measures at intervals of two or three months are compared to the baseline to show both a child’s response to the positive parenting and the post-trauma support provided by the adults in the parenting role.

The eight parenting needs are as follows:-

- Primary care and protection,

- Attachments and close relationships,

- Positive self-perception,

- Emotional competence,

- Self-management or self-efficacy skills,

- Resilience,

- A sense of belonging and

- Personal and social responsibility.

The Cairns (2003) model offers a simple yet sophisticated framework for understanding a child’s progression from trauma-induced stress to recovery. This involves providing a safe starting point in a stable environment where the child can experience stress reduction (stabilisation), then a phase of processing the psychological or physiological reactions resulting from the maltreatment (integration) and later to a point where he or she can begin to achieve emotional adjustment to the negative events which have been experienced (adaptation).

As this article is to outline background, rationale and methodology, for ethical considerations, test data is used for a fictitious ‘Peter’ in figures 5 and 6 below to illustrate how the results are presented. The baseline in blue shows that Peter is likely to need support with P3, (Pillar 3, Positive self-perception) and P4 (Pillar 4, Emotional competence). The orange bars show the results of a second assessment completed after just over a month later, these usually show improvements but will also pick up if things have got worse. What is not included here is the detailed breakdown of the parenting needs upon which the data for the histogram is based. It is this detail which can be used as the bases for the consultation with the psychologist. By identifying and measuring the eight pillars and the trauma phases, the caring adults become more aware of emotional psychological needs.

What makes this process special is the combination of the insights and familiarity which the adults in the parenting role have on their child, with the experience, knowledge of research and theory which the psychologists have. Far from being, ‘one size fits all’ this combination of the carer’s knowledge of the child with the psychologist experience, ensures a unique and agreed care plan for each child. Together they agree on a personalised, responsive and tailored plan with practical tasks which, in the case of Peter below, would include parenting tasks to improve Peter’s self-perception and tasks which would build Peter’s emotional competence. The specific parenting tasks become part of the child’s personal care plan including the tasks agreed from the information in Figure 6, relating trauma. The consultation includes strategies for dealing with self-defeating behaviours, responding supportively to emotional trauma and ensuring that signature strengths are used.

Original research data can be found in Cameron and Das (2019) which will be published later in 2019, in the British Journal of Social Work. This study with 53 children in children’s homes in two areas in England, obtained significant positive results. The probability of getting these results by chance is less than one in a thousand. Cameron (2017) also evaluated the impact of ‘the Emotional Warmth Model of Professional Childcare’ on children in foster and adoptive care and obtained significant positive results with the probability of less than one in a hundred.

These papers confirm that with a research and psychology knowledge base it is possible to provide effective, informed, systematic support for children in public care. Further research and evaluation would be needed to separate the impact of the five components employed in the model, these are:

- Training covering the psychological theory behind each pillar plus parenting style, the positive psychology on strengths, the dynamic maturational model of attachment, trauma awareness, dealing with challenging behaviour, observations and methods.

- Evaluation: The systematic baselining and ongoing evaluation of each child’s parenting needs, strengths, and level of emotional trauma. The results are used to inform the next stage of the model, consultations.

- Consultation: here the job of the psychologist is to ensure that theory and research combined with the comprehensive knowledge and insights which the adults in the parenting role have relating to each of the children in their care. With the baseline and the combination of insights, agree and write up goals, priorities and details of the ongoing objectives agreeing how this translates into the day to day work with the child.

- Day to day work: Going hand in hand with the consultation, the daily interactions between the child and the adult in the parenting role to achieve the agreed objectives. All of which is reviewed and evaluated at the ongoing group consultations so that refinements and improvements can be made to practice.

- Leadership and Management: This too is built into the model, however, that would take an article on its own. Good leadership requires skilful support and oversight to empower those in direct contact with children (rather than undermining them). Maintaining fidelity requires a good working knowledge of the theory. Managers should set clear goals based on what has been agreed in the consultations, agree on priorities and performance management to confirm that work with the child is carried out with kindness and empathy.

Science can explain but can’t replace kindness

Every loving parent instinctively knows that science can’t replace basic human kindness and doing our work has consistently put us in the privileged position of meeting many foster parents, adoptive parents and residential childcare staff who have been the loving life-changing reason for children thriving and succeeding. It is no accident that our approach is called ‘the Emotional Warmth Model of Professional Childcare’ as we too know that enabling and empowering kind adults in the parenting role will change lives for the better. Empowerment also involves calling out the ‘emotional violence’ routinely experienced by children on the receiving end of the misguided practice of ‘maintaining a professional distance’ (see Lemn Sissay’s Ted Talk (https://www.ted.com/talks/lemn_sissay_a_child_of_the_state?language=en accessed 16-05-19). Both scientific research and human intuition are overwhelmingly in favour of the importance of combining a close relationship and evidence-based insights from neuroscience to highlight ‘Why Love Matters’ (see Gerhardt (2004))

We have come a long way since the boy king made his £600 endowment. With the development of functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) we are now able to look at the living active brain, without having to cut open a person’s head, see Dr Martin Teicher, (2016) for example. Our knowledge and insights have far exceeded the slow pace of legislative and policy change, but you can help that change happen today with the young people in your care, start using that ‘Yellow Sock Test’ and make your practice evidence-based rather than opinion-based.

Colin Maginn © 2019

Colin Maginn is a childcare consultant and director of The Pillars of Parenting.

E-mail [email protected]

About Colin Maginn

Colin’s professional life has involved working with children in public care. He was a manager at Barton regional secure children’s home for four years, then he was a manager at Orchard Lodge in London also a regional secure children’s home. Colin then opened and ran ‘Ingleside children’s homes’ in London for about twenty years and it was there that the ‘Emotional Warmth Model of professional childcare’ approach was developed with his colleague, educational psychologist, Dr Séan Cameron.

Colin believes that practice should be evidenced-based, grounded in psychological research and theory and delivered with kindness and warmth. Colin jointly wrote a book with Dr Cameron on their work, (Achieving Positive Outcomes for Children in Care) he has also published peer-reviewed papers and articles in the sector press (see below). Colin has presented at conferences in London, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Cork in Ireland, Berlin, and Atlanta, U.S.A.

Illustrations

Figure 1: King Edward VI. Reproduced with permission from:

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Figure 2: A Bluecoat Boy standing in front of New Hall, Christ’s Hospital, London. Drawn and printed by HH Collins & Co, 1854 to celebrate the Duke of Cambridge becoming President of Christ’s Hospital. Coloured Lithographic Print reproduced here, Courtesy of Christ’s Hospital.

Figure 3: Pie chart showing category of need of looked after children admitted to care from March 2017 to March 2018. From Government statistics covering from the 31st March 2017 until 31st March 2018 ( https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/children-looked-after-in-england-including-adoption-2017-to-2018 accessed on the 5th May 2019)

Figure 4: Page 3 from ‘A country that works for all children’ The Association of Directors of Children’s Services (ADCS) (2017) ‘A Country That Works for All Children’ https://adcs.org.uk/assets/documentation/ADCS_A_country_that_works_for_all_children_FINAL.pdf accessed on the 6th May 2019.

Figure 5: Peter’s parenting needs histogram generated by the online Pillars of Parenting progress and development checklist, using test data.

Figure 6: Peter’s adaptive emotional development histogram generated by the online Pillars of Parenting progress and development checklist, using test data.

References

Cairns, K. (2003). Attachment, Trauma and Resilience. London: British Association for Adoption and Fostering.

Cameron, R. J. and Das, R. K (2019) ‘Empowering the residential carers of looked-after young people: The impact of a psychological model of professional childcare.’ British Journal of Social Work (in print).

Cameron, R.J. (2017) ‘Child Psychology beyond the school gates: empowering foster and adoptive parents of young people in public care, who have been rejected, neglected and abused.’ Educational & Child Psychology. 34 (3), 75-96

Gerhardt, S. (2004) Why Love Matters – how affection shapes a baby’s brain. Routledge.

Hannon, C., Wood, C., and Bazalgette, L. (2010) ‘In Loco Parentis’ Published by Demos, London. ( https://www.demos.co.uk/files/In_Loco_Parentis_-_web.pdf)

Higginbotham, P. (2017) Children’s Homes – A history of institutional care for Britain’s young. Pen & Sword History – Barnsley UK.

Loughton, T. (2018) ‘Storing Up Trouble – A postcode lottery of children’s social care’ All Party Parliamentary Group for Children. Publisher: National Children’s Bureau London.

Perry, B. (1995) ‘Childhood Trauma, the Neurobiology of Adaptation, and “Use-dependent” Development of the Brain: How “States” Become “Traits” ’ Infant Mental Health Journal, Vol I6, No.4, Winter 1995

Teicher, M.H. (2016) ‘Annual Research Review: Enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect’ Journal of child psychology and psychiatry Vol 57 Issue 3 pages 241-66.

The Association of Directors of Children’s Services (ADCS) (2017) ‘A Country That Works for All Children’ (https://adcs.org.uk/assets/documentation/ADCS_A_country_that_works_for_all_children_FINAL.pdf

The National Audit Office (2019) ‘Pressures on Children’s Social Care’ (https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Pressures-on-Childrens-Social-Care.pdf page 6. Accessed 8th May 2019)

The National Audit Office (2014) ‘Children in Care’ (https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Children-in-care1.pdf).

Wood, A. M., Linley, P.A., Maltby, J., Kashdan T.B. (2011) ‘Using personal and psychological strengths leads to increases in well-being over time: A longitudinal study and the development of the strengths use questionnaire.’ Personality and Individual Differences 50 (2011) pp 15-19

Additional reading

Cameron, R.J. and Maginn, C (2009) Achieving positive outcomes for children in care London: Sage.

Maginn, C. and Cameron, R. J. (2013) The Emotional Warmth approach to professional childcare: Positive Psychology and highly vulnerable children. In: C. Proctor and A. Linley (eds.) Positive Psychology: research, applications and intervention for children and adolescents. London: Springer.